This story was first published in the Fall 2016 edition of the Gustavus Quarterly.

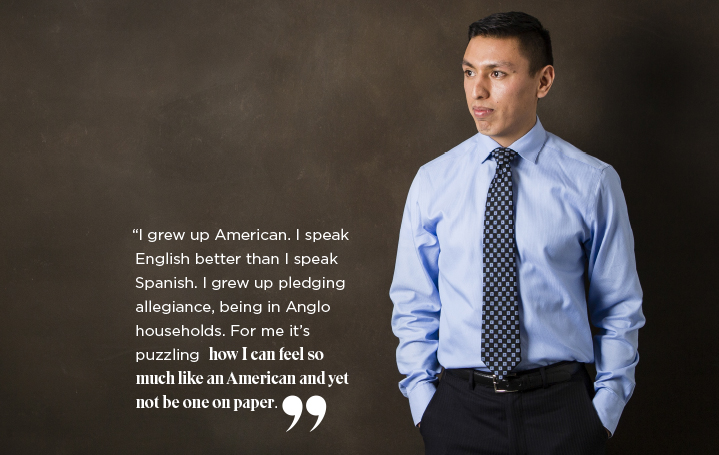

The day in June when the Supreme Court announced a deadlock on giving legal status to undocumented parents with resident children, Antonio Gomez stopped by campus and casually ate a cookie. Though the Court’s decision affected his family, he was gracious and understated, deliberate in his movements and words, as he sat in a Gustavus staff office and talked about it.

His own status under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) remained intact—brought to the U.S. as a child, he can live and work here legally as of today—but politics are shifting sands. DACA, for instance, is the result of the DREAM Act (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) failing to pass Congress.

“I’m a bit nervous, but I believe in America,” Gomez said of the Supreme Court’s split decision. Though if he was nervous, there was no real way to know. He presented no visual trace of it.

•

It was January, 1997 when Gomez and his older brother Ismael stepped off the Greyhound bus at the bottom of College Avenue in Saint Peter. They were seven and nine, and had crossed the U.S.-Mexico border dressed as girls, pretending to be asleep in the back of a van. It had taken them 23 days to get to Saint Peter from Leon, Guanajuato, Mexico, to their mother.

She had worked in a southern Minnesota cake factory for 16 hours a day at less than minimum wage to pay for their crossing. The toll on her cannot be quantified, but what she paid in dollars for their crossing was $6,000. For her, it was worth it for the chance to give them all the American dream.

The family lived in Le Center until the 1998 tornado left them homeless. They relocated to Le Sueur, where, by age 13, Gomez was working: “Carpentry, masonry, landscaping, shingling. My brother and I built pole sheds.” Yet they wanted to go to college. “We wanted the things our Anglo friends wanted,” he says. It was agreed that he would go first. Gomez’s brother and mother worked to send him to community college. They paid in cash because undocumented students cannot get federal or state financial aid. He relied on friends for rides because his undocumented status meant he could not get a driver’s license. Sometimes he drove anyway, because it was the only way he could get there. “When you’re undocumented, it’s difficult but there are times when you have to lie.” Few at community college stepped up to help him, he says, and his undocumented status made him afraid to ask.

But the risk paid off in class. “I started putting it together—that everything could be argued and the person who did the most research won.” As an undocumented Latino kid in white Minnesota living on high alert, he understood. “Everywhere I go, my brain automatically switches to the other side on purpose, for survival.” College showed him the value of this skill, and gave it a name: analysis. Becoming aware that he was good at something so valuable was a transformative and empowering experience. “That’s one important thing about education—once you know a little more about your rights, you feel like you have power.”

A community college instructor helped him find a Gustavus admission rep. He can barely say her name—Violeta Hernandez ’07 (who also came to Minnesota from Mexico as child)—without tearing up. “She genuinely cared. She really believed I belonged at Gustavus,” he says. On his visit to “that college on the hill” just blocks from where he had been dropped off 16 years earlier, he began to believe she was right. “People greeted me with a smile. It was warm. People went that extra step to try to figure out how they could help me.

“Coming from a place where I was treated as a worker—where I was yelled at, where I didn’t expect any respect—at Gustavus I felt like I was equal to everyone else.”

•

“He was more mature than the average student,” says his Spanish composition instructor, Mayra Taylor. “He was focused and had a tremendous drive to succeed.” But he lived without the privileges of other Gusties. He worked all night at a dairy farm, often showing up to class exhausted. He still had no driver’s license or possibility for financial aid. The pressure was excruciating. “I could not sink. I had to do it. If I failed, my family failed,” he says. A few Gustavus mentors knew his situation and would remind him of the resolve he brought to life’s challenges, and how this would serve him well in the future if he could just get to graduation. They kept him going.

“The undocumented students I have had are self-motivated and passionate learners, but also very realistic. Sometimes they juggle working full-time to provide for their families at home, in addition to taking a full load of courses in order to remain in good academic standing.” —Angelique Dwyer, professor, modern languages, literature, and culture

Still, every semester was a financial struggle. Despite Gustavus scholarships and his family’s help, he constantly came up short. By his third year, he had exhausted all options. “I started thinking about my life,” he says. “I thought, I really want to finish school. I don’t want to beg. But I have a story to tell.” He posted on a blog about his story as an undocumented immigrant. It should be no surprise to Gustie alums that donations from throughout the Gustie community came through. And something else: “That’s when I realized I should be proud of my story.”

•

In 2014, his final semester at Gustavus, DACA gave Gomez the temporary legal status he has today. He got a driver’s license, and a state grant for college. “I finally had some wings,” he says. “I joined some groups. I started staying up late with friends, looking at the stars at Gustavus, doing little things that I never really got to be a part of.” At a picnic celebrating the Saint Peter sister city of Petatlán, Mexico, Gomez met Larry Taylor of Taylor Corporation. Gomez approached him and talked about how he paired his business major with Spanish to master his first language. Taylor and his wife, Thalia, longtime supporters of Gustavus international and immigrant students, were impressed. “I thought, this kid is on the ball,” Taylor says.

Taylor got him a job interview, but Gomez sold himself. He was hired as a sourcing analyst for Taylor Corporation, and he set about doing what he always does in stressful situations. Says his mentor and former supervisor, Andrew Bittner, “Adversity taught him to train harder, to put in more hours, to lean into the expertise of others.” In just six months, Gomez built “a significant reputation within our business unit,” and became an inspiration to Bittner personally. “In all that he does, Antonio is most interested in how he can affect societal good, how business is not just good in itself but good because of the potential societal benefits it can create.”

“It’s not about me, it’s about the community,” Gomez says. That includes his family, whom he supports financially, Gustavus, and other undocumented Latino people in Saint Peter and the U.S. DACA is an executive order that can be overturned by any new administration. Gomez, who now manages shipping and freight for multiple Taylor Corp. companies, has successfully become the American dream his mother sought, in the only country he has really ever known. He is still “undocumented”—DACA is just a two-year bye—so he exists in citizenship limbo. “I might be okay, but there are millions of people who might not,” he says. Then he pulls back and calmly folds his hands in his lap. “I have found a way to focus in my work. I know it’s all going to change at some point.”

What will he do then? “I’ll readjust and do what I need to do,” he says.

•••

There are an estimated 665,000 people living and working in the U.S. with DACA approval. There are an estimated 6,000 who live and work with DACA approval in Minnesota. A 10-year goal for Gustavus—a college founded by immigrants—is to increase access for and retention of students of diverse backgrounds, including students like Gomez.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.