Sarah Ruble, Professor of Religion at Gustavus, on her love of history, Free Methodist background, book on American Protestant missionaries after World War II, and innovative adult Sunday School video series on Race and Christianity in the United States, as well as white evangelicals’ support for Donald Trump and why learning about religion matters both generally and at Gustavus specifically.

Season 5, Episode 5: History, Religion, and Adult Sunday School

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of Gustavus Office of Marketing. Will Clark, senior communications studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast, and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

The history of religion and race in the United States is both fascinating and fraught.

Most consequentially for that history, I think slaveholders found justification for slavery in the Bible. And as the escaped slave turned abolitionist and Black leader, Frederick Douglass, observed, “Religious slaveholders are the worst.” Moreover, as Douglas and other abolitionists, Black and White, highlighted in withering words, “Southern and northern White Christian churches were complicit in slavery’s existence and continuance.”

Yet simultaneously, abolitionists were themselves fired with religious zeal and attacking what they saw, is the most horrid sin of the land. One person that can save us who has been thinking a great deal about religion and race in US history in recent years is my colleague, Sarah Ruble, of the religion department. Prompted by the white nationalist rallies in Charlottesville, Virginia, Sarah had the brilliant idea to create an adult Sunday school video series titled, Race and Christianity in the United States, a series informed by both her academic expertise and her own Christianity.

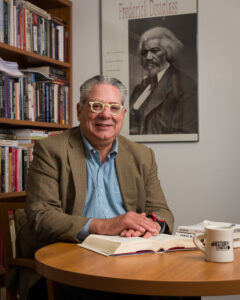

Sarah holds a BA in history, I’m happy to say, from Seattle Pacific University, a master of theological studies from Duke Divinity School, and her PhD in American religious history from Duke University. She joined Gustavus in 2007, and is without doubt, one of the most highly respected faculty members on our campus. In addition to her teaching, she serves as the college’s faculty director of assessment, and is active as a scholar as well, serving on numerous conference panels.

And authoring the excellent book, The Gospel of Freedom and Power: Protestant Missionaries in American culture after World War II, published by The University of North Carolina Press. Because of recent events around race in Minnesota, in this country, and then also my own longstanding interest in the place and role of religion in 19th century US history, I’ve been looking forward to speaking with Sarah for quite some time for this podcast.

So, welcome, Sarah. I’m just thrilled we had the chance to do this.

Sarah Ruble:

Well, thank you. Thank you for having me. It’s good to be here.

Greg Kaster:

My pleasure. I know a little bit about your background but not as much as I’d like. So, why don’t we start there and talk a little bit about where you grew up and how you found your way first into history as a history major? And then, from there, into your work both at the Divinity School in Duke?

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah, absolutely. So, I grew up in Washington State, spent the first 12 years of my life in Seattle, Washington. And then, my family moved to Eastern Washington, which is a pretty big cultural move, in Washington. Eastern Washington is the desert part of the state. And then, went back to Seattle Pacific University to do my BA work. The question about history is interesting. I always loved stories as a kid. I would make up stories.

I’d write stories. I loved reading stories. And I think just there was an intuitive that I understood that history was a great story, that you were trying to put together stories that explained things, whether they explained things in the past or explained things in the present. I mean, I was the kid… I remember in middle school reading books about Watergate for fun and rereading them, and rereading them.

I was the kid who would watch the PBS documentaries and just found… I think found it helpful because I really felt like history… there was just a sense that it helped explain the world around me. And I loved that about it. And I’m a part of it, too. I don’t know, I can’t remember people guiding me here. I don’t know if it’s just what I found. But I think also, historians tend to be really good writers.

Greg Kaster:

I agree with that. Thank you. And yourself included, of course.

Sarah Ruble:

And so, part of it was just good reading. And I enjoyed reading, and there were good things to read.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, keep going. But you’re reminding me… I mean, I think the point about stories is really important. Sometimes, students ask, how did I get interested in history? Well, yeah, sure there were some teachers. But I know, I think my interest came from these “war stories.” My father, who had been in World War II, would tell my brother and me. I remember as a kid, “Put your war helmets on, boys.” And they were actually anti-war, and they were all about contingency.

The role of, “This is why it happened, and I wouldn’t be here, and you wouldn’t be here.” It’s not exactly what we want to hear when you’re six years old. And then, he’d pretend to be some guy down the bathtub drain, which I’m sure many parents has done making up these stories. So, anyway, I think the point about stories is really, really important. So, you’ve found yourself majoring in history. I mean, did you know that when you’re going into college that you’re going to do that? Or did it happen-

Sarah Ruble:

I didn’t. So, I knew I would major in history. I had no idea where that would lead. And then, what ended up happening… so, Seattle Pacific University is a college affiliated with a religious denomination. I grew up in the Free Methodist Church, which we’ll probably talk about more. And so, you end up taking courses in there. It’s a theology department. And one of the professors in the theology department did most of the church history courses.

So, the history courses were in the history department, the US history… I took a lot in African history. But then, the church history courses were in the theology department. And also, the same professor, a man named Rick Steele, taught a lot of theology courses. And I found myself just very interested in the history of ideas but more of the cultural history. I mean, the cultural history of Christianity. I didn’t know what that meant.

And one day, Rick Steele took me out to lunch and said, “What are you thinking of doing with your life?” And I was, “I don’t know.” And he said, “Studying the history of the church, religious history, is a thing you can do with your life.” And that was just the most phenomenal thing I’d ever heard. Because I really did enjoy that place where you thought about how ideas play out on the ground among, sometimes elite people, but more often, non-elites, and how they get translated and how they get practiced.

And so, it was really at that moment that I decided I wanted to go and pursue a PhD in religious history. And that then led me to having to make a couple of decisions. And one of them was about whether I wanted to go straight into a PhD program or not. And I decided I wanted, in some ways, just a little bit more time and grounding in both, just some basic theology, which I found interesting in its own right.

And also, just some more time to get a little bit better sense of what I might want to study if I did pursue a PhD. So, that led me to do the master’s of theological studies and ended up working as a master student with a man named, Grant Wacker, who’s the American religious historian there, or was at the time. And then, staying there when I had the opportunity to do so.

Greg Kaster:

Well, I know his work. What was he? I never met him. What was it like to work with Grant Wacker?

Sarah Ruble:

He was wonderful. He still is. He is so wonderful. So, there are a number of things about Grant that I really appreciated as a scholar and as a person. One of which is that he really invested time in making his cohort of students, a true cohort. We still, when we go to conferences, go out to desert with usually Grant, one night, all together. And we help each other, and we work with each other. And it was so collegial.

There are people who have wonderful graduate school stories, but there are people who have terrible graduate school stories. It’s cutthroat repetitive. I had the wonderful story where people helped each other. They supported each other. We found things for each other to help with our work. And that was very much Grant. I mean, it was not a place where he wanted people showing off. And I really appreciated that.

The other thing that working with Grant really instilled in me was that, it is good fortune to have the luxury of doing something like a PhD. And if you have that luxury, you have responsibility to do your work well, but also, to make it as accessible as possible while still making it rigorous. Grant likes to say that you should pick someone in your family to write for. And that if that person can’t understand what you’re saying, then you’re not doing a good enough job of saying it clearly, and you’ve been given the time to say it clearly.

I mean, this is part of what you get for being in a PhD program, is that you were being given the gift of time to learn to say things clearly, and you need to say them clearly.

Greg Kaster:

I love that. First of all, I love that idea, about thinking about a family member. And maybe I’ll start using that in my teaching as well, with teach writing, but that’s such an important point. And there’s still historians who write primarily… not just historians, for other scholars, right? But I’m thinking of our own alum, the distinguished historian, James McPherson, and his great civil war story. Who, when his Battle Cry of Freedom came out and won the Pulitzer, I mean, he writes about this. He took some criticism from fellow historians.

Maybe it was envy. But this is, “You’re a popularizer.” I mean, it’s a fabulous book that anybody who’s educated and interested in the subject can read and understand. And I’ll put a plug in for your own book, certainly, but also your own writing, which is incredibly clear. And maybe, some of that has to do with Professor Wacker. The other thing that I love what you said earlier is that the professor, I forget his name now, but the professor-

Sarah Ruble:

Rick Steele, yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, who said, “This is something you can do.” Some of us are lucky enough to have had that experience with a teacher but just how much that can change your life.

Sarah Ruble:

Oh, absolutely, right? And I think both the affirmation of… that you personally can do this, and this is an available option in the world. I think one of the gifts of great teachers is looking at you and saying, “I see this thing in you that you may or may not see, but I’m going to name it for you, so that you really do know it and that it’s a formed in you.”

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s it. That’s exactly right and well said. I’m going to name it for you. So, you mentioned, so you grew up in the Free Methodist Church. Is that right? Is that what you said?

Sarah Ruble:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yup.

Greg Kaster:

And can you tell us a little bit about that? I mean, a little bit about that denomination?

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah. So, the Free Methodist denomination actually came about in 1860, basically, and it was one of the splits owing in part at least, to slavery. So, at the time, the Methodist Church in the north still did not have as strong of a stance against slavery as some people wanted, that my folks, I guess, the Free Methodist, were in upper state New York, and thought there should be a stronger stance.

They also felt like the mainstream Methodist Church have lost some of the Wesleyan, coming from John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, teaching on sanctification or belief about how godly people can become in their life. The other thing they didn’t like was that, in the Methodist churches in the 1850s and 1860s, rich people could rent pews. Well, anybody could rent pews, but rich people rented pews. And they got the best pews.

And so, they split off because they wanted a stronger anti-slavery stance. They wanted stronger teaching on sanctification. And they didn’t believe in the rental of pews. The denomination, like a lot of denominations in what’s called the Holiness movement, they’re part of that, was in some ways, a radical movement for its first 30 years. So, for example, the leaders of the movement didn’t think you should wear gold jewelry. Oftentimes, including wedding rings, because if you have that money, you should be giving it to the poor.

B.T. Roberts, who was the founder of the denomination, wrote a tract in 1890 about why you should ordain women. But then, what happened, and this happened in various parts of the Holiness movement, was that the first generation died. And they kept a lot of the rules without the radical edge. So, a lot of what they had originally been, things about caring for the poor, identifying with the poor, got translated into being, “Gold was worldly.”

The problem wasn’t that it was anti-poverty or was not hospitable to people who might be in poverty, but that you were just being worldly. So, by the time I came into the Free Methodist denomination, I think it aligns with American evangelicalism. That’s where it fits. But it had been, for a while, having some internal conversations about where it wanted to be in terms of its own sense of its history.

And I think trying to reclaim some of what we would now call social justice roots and figuring out where it fit and did not fit within broader American evangelicalism. So, I grew up in the church that we attended until I was 13, was the church my parents both grew up in. And there were Free Methodist pastor in the 1960s, was counseling the men of the church about being conscientious objectors in Vietnam, which was not the normal white evangelical position.

Now, having said that, I also had relatives in the church who were somewhat to the right of the John Birch society. So, it was this odd group. But I think the other thing to say is that, it was in Seattle, Washington, which is not a particularly churched part of the country. So, the church I grew up in didn’t have a sense of itself like I think some… even white evangelical groups have in some parts of the country, of being dominant in society. It knew it was weird, and it got that… most people in Seattle don’t go to church on Sunday morning.

That’s not an expectation that people have. And you don’t have the sense that we should be in charge of the culture in the same way that I think evangelicalism can have, again, in other parts of the country. So, it was a particular slice of the evangelical world to grow up. And that was pretty formative for me.

Greg Kaster:

That’s also interesting to me. Was anyone in your family a pastor?

Sarah Ruble:

No. No. No pastors, teachers.

Greg Kaster:

Teachers, okay. I don’t know enough about the… I mean, are there many Black members of this denomination? I don’t mean just in Seattle, but-

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah, no. Although, oddly enough, not in America. The domination is very small. I think there are maybe… I’m going to say this wrong, and some Free Methodist somewhere will correct me. But I want to say there are 40,000, 50,000 Free Methodists in the United States. There are more Free Methodists in Africa than there are in the United States. So, yes, there’s Black Methodists. But in terms of the movement in the United States, it’s still primarily dominantly a white movement.

Greg Kaster:

Okay. Well, here we are, you’ve made this… again, I think and I really mean it, brilliant, absolutely brilliant idea, to create this adult Sunday school video series on race and Christianity in the United States. And while your graduate work, your dissertation, didn’t focus per se on that topic per se, here you are. And I wonder if you could say a little bit about how you become more interested in that topic, both as an individual, as an academic and as a Christian?

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah, absolutely. So, I think there’s a number of things. One of which has, well, been in my field. I think a longer conversation, but one that certainly got amplified by the 2016 election, about how we think about evangelicalism in the United States. So, in the field of religious history, the dominant readings of evangelicalism really came out in the 1980s, 1990s with folks like George Marsden, Nathan Hatch, to some extent, Grant Walker, who really defined both American fundamentalism and evangelicalism in very doctrinal or theological ways.

And a lot of us, interestingly, who studied with these folks… oh, Mark Noll would be another major name.

Greg Kaster:

For sure, Mark Noll. Right.

Sarah Ruble:

All of them who were themselves identified with some version of American evangelicalism or a reformed confessionalism. So, they tended to attract students who had either sympathies with, or like me, came from evangelical or reformed backgrounds. And I think for a lot of us, again, I’m not atypical here, came out of forms of evangelicalism that we grew up believing we’re relatively hospitable to at least a moderate politics, where if not progressive on racial issues, we’re interested in talking more about race and systematic racism, and those sorts of things.

And then, I think over the course of the 2000s, but again, amplifying is towards the 2016 election, there began in my field to be a lot of people who are saying, “White evangelicalism is very White. And maybe we need to take the whiteness of evangelicalism more seriously and think about the ways we’ve been telling these stories that are really focused on theology, the theology of fundamentalists and evangelicals, and to some extent, gender, and really begin to interrogate the racial dynamics.”

So, I wasn’t certainly doing my scholarship on the forefront of that. But I was involved in some of those conversations and knew a lot of people who are doing some really great scholarship in those areas. And part of what I think drove me in that conversation is my book. My book is about the American missionary movement. And I look at different public discussions of missionaries.

And for my public discussion of missionaries, I looked at Christianity Today, which has long been considered the flagship magazine of American evangelicalism. And I argued in this book, “Well, this magazine is more progressive on some of these issues around problems of colonialism and imperialism, and racism. And isn’t this nice that evangelicals are a little bit more on the forefront of this than you might think?”

And as these other discussions in my field start coming up and the 2016 election happened, having to think with my version of, or my assumptions about what really evangelicalism was about and the primary voices of evangelicalism, was I right about that? Or was I picking maybe elite or a non-representative strata of it and taking it as more representative than it really was? So, I think from a historical background, that’s where I came at it.

And then, I do a fair bit of speaking in churches around the area. And I just recognize that a lot of people are actually both interested in the topic of race and Christianity. And also, just don’t know a lot about it. And that it’s a hard one to talk about in part, because people, even if they have a sense that there’s something wrong with race, and particularly race in the church, they don’t really know enough to have a good conversation. So, all of that came together.

And then, the other thing that… and this is just a piece of professional autobiography, was that after my first book, I had a child. I was trying to figure out next projects, and I kept getting asked to do these long encyclopedia articles for things like Black, right? So, the 20-page cover 400 years of history in this. And I realized that I was really pretty good at it to the extent that I have a distinctive act and a gift.

It might actually be the ability to synthesize other people’s primary research. I enjoy the primary research. I can do it. But this was something that I was really good at and enjoyed. It was an interesting intellectual exercise for me. So, all of that came together after Charlottesville. And I thought, “Okay, given where my field is, given the fact that I think white Christians specifically need to be able to have a better conversation about racial issues, given my skillset, what can I do here?”

And I thought, “Well, I can probably synthesize scholarship on this issue in a way that… and present it to a group of people, white Christians, that I know pretty well.”

Greg Kaster:

It’s so great. I mean, I’ve looked at a few of these, and that’s a really helpful explanation of how you got into this. The videos are just terrific. I haven’t looked at all, eight totals, is that right?

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

And they’re about what, 20, 30 minutes? And that skill of synthesizing, which you are very good at, and which I highly value and aim for as well in my own work, that is, of course, important to teaching as well. And that’s really what you’re doing, right? You are in the videos. I think you’re in all of those, as far as I know. Tell us a little bit about the process of making them and also distributing them, if you would?

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah, absolutely. Well, first, I have to say, this is one of those projects where there were some contingent things where I’m very fortunate. One of which is that my husband… this is a very good story here. So, after my husband and I got married, he went back and finished his degree in his early 40s. And as part of that, had to take an arts class. And the arts class he took was from Dr. Priscilla Briggs on video art.

And he really enjoyed it. He also was getting a degree in computer science. And so, when I came home one day and said, “So, hypothetically, if my next project was a video series, could you do the editing for that?” And he said, “Sure.” So, the process really was that I spent the first couple of years writing, which meant going through… some of this was history I knew pretty well. Some of it was stuff that I knew a little bit about but had to do much more digging on, and then writing the scripts.

I think we did the first four. We did them in two batches. So, we did the first four. We actually went to the church I attended here. I attend here in St. Peter and set up a green screen and just spent a couple of days filming them. We bought a teleprompter, so I’m reading scripts. It is teaching. But when I teach, as you can tell on this podcast, many more verbal tics than you would want in a video series. And then, Todd went through and edited them, and put in the wording where one outlines and those kinds of things.

And then, I went on a hunt for Google images that you could use for free and put those in. So, it was very much an in-house thing. Part of the decision making there early on was that I knew I wanted to do it on YouTube for two reasons. The first is, I wanted it to be free. Knowing church life, there are certainly churches that can pay for people to come in and speak. But a lot of churches don’t have adult Sunday school budgets.

And so, I wanted it to be free for anybody who wanted it. And I also didn’t want it to be platform. So, I wanted both mainline people to be able to use it and evangelicals to be willing to use it. And given the way the church landscape is now, if you publish with certain publishing houses and not others, that can be a red flag to people on the other theological side. So, that was it. And in distribution, I just started my first set of… I mean, basically, I’m sending emails to church leaders.

I started with Methodists of various kinds because it’s the group I know the best. Basically, district superintendents and bishops and saying, “This is available to you.”

Greg Kaster:

And are you getting feedback? I mean, do you get a sense of how these videos are being received?

Sarah Ruble:

A little bit. I mean, they just all paint out. So, I’ve done the first couple of sessions I did. This is cheating a little bit. I currently attend a Presbyterian Church. So, my presbytery is doing webinars on them. And so, I’ve had a little bit of interaction with those folks. And then, this one was very fun, an Episcopal priest in Michigan found them. I’m still not actually sure how. I need to figure that out. And he and a group of his parishioners watched the first four together and talked about them. And they’re talking to me over Zoom.

So, they’re also probably being polite. But basically, the feedback really has been, “This is helpful because I didn’t know it.” Right? So, both the groups that I’ve had the most conversation with at this point, are groups that they believe systematic racism is a problem. They believe racism is a problem in the church but aren’t sure of the history that underlies it. And so, again, I think it’s that, “This helps explain things that have seemed weird or wrong, or now that I think about them, are strange. And now, I understand a little bit why.”

Greg Kaster:

If our listeners could see me, you could see me I am nodding quite vigorously. I think, because it goes back to what you said some minutes ago, which is, “Man, I really…” I feel this so strongly, including our own campus, everywhere that, if you don’t have the knowledge and that knowledge around the issues of race has to be in some part historical, how do you have a conversation? How do you even begin a conversation? How do you have a conversation that’s useful?

And so, I think that’s a huge contribution of your videos. Tell us a little bit. I mean, I know you started in the colonial period. I think you have a whole one on the slave trade, Atlantic slave trade. Do they come up to the present or are they mostly… go ahead.

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah. Basically, they start in colonial era. The fourth one, which marks the first half, is about the debates about the Bible and slavery. So, it ends with the Civil War. And then, the fifth one starts at reconstruction era of citizenship. And the eighth one ends talking about 2016.

Greg Kaster:

I wonder about 2016. And I wanted to come back to that, and you just gave me the opportunity to do it. Because you know even better than I do, anyone who reads the newspaper knows. I mean, one of the questions that keeps coming up is, how is it that evangelical voters support Donald Trump who is anything but an evangelical, not only not attending church, but just in terms of his own well-documented behavior? And I’ve read all kinds of things about that.

And I wonder if you have thoughts about that. And I don’t mean this to be partisan, but just what does explain that? There seems to be such a gulf between what an evangelical Protestant stands for and what President Trump’s life has been.

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah. So, here, I’ll say that I think the thing I would tell people to do quickly is to go and buy Kristin Du Mez’s new book, Jesus and John Wayne. She’s a historian at Calvin College who’s just written a book that I think I basically agree with. Which is to say that Donald Trump is not actually the deviation from white evangelicalism that we’d like to believe, but he is a manifestation of at least a stream of it. And it’s a stream that emphasizes a particular kind of really dominant masculinity, hence her John Wayne.

And that sees its role as defending certain ideals that have a lot to do with… I mean, some of them are about race. Some of them are about gender. Some of them are about economics. They all go together. And that in the defense of those ideals, it’s not only acceptable, but actually good to be… I don’t know how to put this nicely, a bully, that you need to be very assertive. And you need to win this fight because there’s a sense that we really are in a fight for these goods.

I think that’s right. Now, I want to be careful. There certainly are White evangelicals of all sorts of stripes along the theological spectrum that disagree with that, would disagree with the idea that you should fight, like you should have a fighter like Donald Trump on your side. But again, I think part of what 2016 showed, and this shouldn’t be a surprise to those of us who come out of White evangelicalism or study it, but I think in some ways it was, is that the leaders really don’t speak for a lot of people in the pews.

I think part of what happened in 2016, and I think it’s in a lot of scholarship even that those people like me have done, is that we really thought that Christianity Today and Russell Moore, who’s the head of the Southern Baptists Ethics Commission, and people who teach at Wheaton College in Illinois, speak for evangelicalism. And what I think we learned in 2016 is that a lot of White evangelicals are much more formed in their politics by Fox News than they are by their churches or by elite evangelical organs, and that we were paying attention to the wrong things.

Greg Kaster:

And so, you circled back to a point you were making earlier that maybe you had it wrong or you were focusing on the elites in your graduate work missionaries. Yeah. Boy, I’ve written the title down, Jesus and John Wayne, and I will be purchasing the existence in here. I didn’t know about it. So, thank you. And I think that resonates with me a lot for the following reason. I think there’s been… and again, I’m generalizing.

But on the part of some pundits, at least, if not historians, this way of authorizing Trump politically and culturally, and even President Obama and others, Joe Biden, that’s not who we are. And I find myself saying, “It is who we are.” Meaning, Donald Trump is part of who we are as a nation, if we look at our political history, our cultural history. And this only makes me believe that even more, I love the argument that he’s not deviating from at least a certain strand of evangelicalism, but is very much in keeping with it.

And that we also need to look down at gender, notions of masculinity, manhood, womanhood. Yeah, fascinating stuff. Thank you. Let’s talk a little bit about your graduate work and your book that grew out of it. Because, again, I find that stuff so interesting. First of all, and honestly, thinking, reading, and thinking about your book… when did it come out, 2012 or something like that?

Sarah Ruble:

2012, yeah.

Greg Kaster:

2012, yeah. I mean, maybe because my training is primarily 19th century US history, I didn’t really think about missionaries in this country post-World War II. And of course, they’re there. They’re important. So, maybe let’s say a little bit about that topic, what you found, what’s your book argues?

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah. So, the book looks at conversations about missionaries, a mix of American missionaries serving abroad, but in American culture. And I look at a few different groups who are talking about missionaries after World War II. So, mainline Protestants, evangelical Protestants, anthropologists. And then, I look in specifically novels, but I have one chapter that’s really on gender and missions.

And what I end up arguing is that, conversations around missionaries, was a site where you could see all sorts of different types of Americans trying to sort through the new realities of post-war American power. And because simultaneous commitment, both to a sense that other people should be free and that we as Americans really know what’s good for the rest of the world. And that we were trying to hold those two together, that we want to acknowledge that people should be free.

People abroad should have autonomy. And yet, in all these various ways, we really feel like we have the answers, and we know what should happen. And that missionaries were definitely the only ones talking like that. But people talking about the missionaries were also wrestling with their own sense of those competing commitments. Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Essentially, yes, this idea that you’re free to be like us, basically. I mean, I don’t know if you would call it cultural history, cultural intellectual history. It sounds like it was fun to research too the sources that you used. And I highly recommend the book, it’s just terrific. It’s a fun and interesting read. And there are connections, just as I learned reading your book to the 19th century. And same thing with manifest destiny, we need to bring democracy and freedom.

And of course, what that means is American-style democracy and Protestantism, is what it means to those poor benighted Catholics.

Sarah Ruble:

And some of the question, I think… I mean, as I think what happens after you’re done with a dissertation or a book you look at, I had this moment of thinking, “Wow, what I’ve really just ended up spending years of my life arguing is that we, human beings, like to have things the way that we like them.” It might just be a truism. But I think whether it’s the 19th century or the 20th century, that changes when you’re talking about people with extraordinary amounts of power, right?

It’s not just that we all have preferences, but it’s that some of us can make our preferences manifest in the world, and how do we think about that.

Greg Kaster:

That’s an excellent point, which also fits perfectly with the next question I was going to pose to you. And I realized this is may be in some ways, difficult to answer, especially since you’re hearing it for the first time now. But I’m just curious, given especially the video series you’ve made, but also the earlier work and your thinking about what has happened recently, what do you feel you’ve learned or what insights have you gained, if any, into the issues around race and religion specifically in US history?

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah. No, it’s a really good question. I mean, this isn’t a new thing. But I think to me, it’s just absolutely pivotal that… well, a couple of things. One is just how important money is in all of these conversations. I mean, speaking now as a Christian, talking to Christians, I think sometimes we don’t like to talk about that, which is bizarre given the book that we say we adhere to, which talks about it constantly.

But just the reality that I think, particularly in a lot of Christian conversations, I feel like we try and have these very… what we think of as high-level theological conversations. So, about grace and forgiveness, and those sorts of things, which are all good words without dealing with realities like money and power. And I think that the country has also… I mean, there are a lot of Christians in this country. So, to some extent, how Christians have a conversation has a lot to do with how the conversation goes nationally.

But I think, to me, I just kept coming up against that, that if we’re really going to talk about this issue, we have to be willing to talk about money. Who has money? Who has access to money? Who has power? Who has access to power? And those are really hard conversations. And it’s not surprising to me that we keep reverting to conversations about words that are a little bit more abstract.

Greg Kaster:

Yes. And I mean, yeah, you can’t. Just even thinking about race, so I was speaking to some people for the podcast, some other historians. But how do you talk about race without talking about issues of economic, right? And then, the related power issues? I mean, I don’t know. This is not necessarily race and religion, but reading about the current Attorney General, William Barr, and also thinking about who might be the latest addition to the Supreme Court.

I mean, the line between church and state seems to be eroding. Is that a fair statement?

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah. So, part of what I think is happening is that… listen, try and do what you think as a historian. So, I think for a lot of American Christians, for a while, mainly Protestants, but now Catholics, are… I think are white Catholics. And again, this is a very white conversation. White Protestants and white Catholics, they were simply culturally dominant, right? So, in the 19th century, white Protestants aren’t necessarily the numeric majority, if you count who’s in church on a Sunday morning, but they hold cultural power.

They hold economic power. They hold political power. And then, in 20th century, Catholics joined them. And it’s easy to talk about the separation of church and state when you get to decide what that means. And you’re pretty sure that whatever happens with it is going to end up being something that you like. So, for example, Kathleen Flake, who’s a historian of Mormonism, makes this argument brilliantly.

She said, in the 1890s and early 1900s, “White Protestants were very happy to tell Mormons that they had to make a decision between serving their God and being good loyal Americans because white Protestants were pretty confident that they would never be put in that position, that the two would never conflict for them.” I think 100 years later, what’s happened is that the culture has shifted for lots of complicated reasons.

And that there are some white Protestants and white Catholics who are very concerned that they no longer are the ones who get to determine where that line between church and state is if they just let it happen to them. So, they are working very, very, very hard to be the ones in charge of determining where that line is.

Greg Kaster:

That actually makes a great deal of sense to me. Turn that into an op ed or something if you haven’t already. But no, seriously, it does. It helps. I know what you said. Listen, I’ll preface my remarks this way. You may remember, Sarah, it was years ago. I don’t remember how many years ago. You were teaching in a classroom before me at Gustavus. And I came in and scrawled all over the board, at least as I remember. And you’re handwriting, you were still there. You’re finishing up class.

But all this stuff about Harriet Beecher Stowe, all this stuff just spoke to me, because I was teaching my American Life’s course after your class, and it was about… and I’m teaching it again this semester about Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a daughter of the great Presbyterian Minister, Lyman Beecher. I was going to save the West from Catholicism, Brother Henry Ward Beecher. And then, Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. And there is just no way to understand 19th century American history, those specific, without looking at religion and evangelical Protestantism, and yeah, Catholicism as well.

I would even argue there’s just no way to understand anything about US history without looking at religion, whether you’re a religious person or not. And I sometimes just think about it. I find myself, on the one hand, fretting about the blurring of the line or the erosion of the line between church and state. But then, also, I’m just utterly fascinated by how evangelical Protestantism in particular played out in the 19th century, especially around reform, and especially around slavery and abolitionism.

Sarah Ruble:

A part of it then becomes interesting to me, and this is now somewhat as a historian but more as a Christian, one of the things I think about a lot with that history is that the question that I wish, again, white Christians would ask more, is our constant trying to get power. It’s not only good for the country, but is it good for the faith? When you look at most… well, to me, the most positive stories about Christianity in the United States, not all of them.

But many of the most positive stories involved the Black church. And part of the reason is because they weren’t trying to be in charge. They were trying to simply be taken seriously as citizens. They were using their faith in politics but not from a position of power. And I think that’s telling that when we look at good examples of people using faith in politics in this country, the ones that were celebrate the most don’t come from people who already occupy huge positions of power.

And again, as someone steeped in the Bible, that shouldn’t be surprising. But for some reason, I think for a lot of white Christians, we keep finding it.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I agree. I mean, I think that makes perfect sense to me. And, of course, exactly. I mean, the idea behind separation of church and state is to protect religion, not to step it out. While we’re on this topic of evangelical Protestantism and reform, we’re sort of on it, you did… and here we are in 2020, the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage, and of course, one of the great activists around that was Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who didn’t live to see it, though her daughter did. You did some work on Stanton and religion. I think was it for your masters?

Sarah Ruble:

Yep.

Greg Kaster:

A shout out to Stanton. Could you tell us a little bit about that work?

Sarah Ruble:

Yeah. One of those things, if I was writing it, I think my thesis was wrong. But I was basically looking at Elizabeth Cady Stanton and trying to situate her religiously. And I tried to argue that she was more of a biblical literalist than… or at least she treated the Bible literally in a way that she was trying to make a pitch to talk to women, to understand what the Bible really said. And that part I think is right. I think I tried to put her in as a commonsense realist, which is a whole complicated philosophical thing that’s going to.

But what Stanton really, I think brought out was the need to wrestle with the Bible. And so, she was the head of the creation of what’s called The Woman’s Bible, which was simply a group of women commenting on passages in the Bible that looked at the role of women. And she got, of course, a huge pushback, because Stanton herself basically said, “The Bible is a book. Its authors are human where it speaks truly about God.”

That sometimes happens when people talk about God, but there’s nothing inspired here, which did not go over well in 1890. But I think what she pushed, and this is I think a good question for people for whom the Bible is an inspired book, is a question about hermeneutics. How do you read this ancient text on for her issues of gender? Because you’re going to have to make some decisions about how to do that. Do you read the first chapter of Genesis where God makes male and female as determinative?

Or do you read the third chapter of Genesis where women are seemingly subordinated to men as determinative? You have to make those choices. They’re interpretive choices. And the Bible doesn’t make them for you. You have to figure those out. And I think she, and other women like her, really pushed that question about, how are you going to use this book? And what that would mean for how you thought about women.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. I find that so fascinating. You’re suggesting this. So, often, she’s presented as… or one thinks of her as a secular person figure. I mean, there she is wrestling with the Bible, as you say, literally wrestling with it, and religion. I just find that so interesting and to link into. I mean, it was easy to… saw a link in religion and link in what’s there. But there, it turns out there’s a great deal there in terms of spirituality.

And sometimes, our students, I’ve learned, confuse church attendance as synonymous with being religious or spiritual. Of course, that isn’t the case. I mean, wow. I could keep going with you for another hour easily because I find this so also fascinating.

Sarah Ruble:

This is just the moment we’ve got.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Well, I was going to say… I mean, one thing I was going to say, all that long preface is, I really would love, and I really mean this too, we can’t plan it here, [inaudible 00:51:44] to team teach with you someday. I don’t know, evangelicalism in politics or something. We could have poli sci and people in it. It would just be great. It would be fantastic. In the couple of minutes remaining, I want to give you a chance to make a pitch for the study of religion and liberal arts college.

Because Gustavus is affiliated with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America. And I confess, when I was looking into Gustavus, I knew I was coming for a job interview, that word evangelical scared me. It had all kinds of negative images in my head. Then, I’ve told many people this story that my advisor, my PhD advisor at Boston University mentioned two distinguished historians. Sydney Ahlstrom, a religious historian at Yale and James McPherson who graduated from Gustavus. “Oh, okay. Whatever, evangelical.”

But I mean, we take religion seriously. All people are welcome at Gustavus. People of all faiths, whatever, atheist, et cetera. But could you just make a pitch for listeners by religion at a liberal arts college?

Sarah Ruble:

By religion, absolutely. So, part of it, I mean, I think there’s two things I would say. One is what we’ve been talking about, right? That I think simply to understand both the country we live in and the world we live in, you have to understand religion. You have to understand religious people. You have to understand how they think. You have to understand what they do. I don’t think the world that we live in make sense without really knowing about how religion works.

And so, part of it is simply trying to figure out how to navigate in the world in which you live. So, I think that’s maybe the more social component of it or cultural, or historical, however you want to think about that. The other thing I will say about religion at a college like Gustavus is, and this is what I think differentiates it from other kinds of institutions. So, you can go to like a college I went to where people that came out of a particular denomination.

There were some clarity of like, “This is what the institution believes about certain religious questions.” And then, there are institutions where religion is really simply an artifact of culture. And you can look at it as an artifact of culture, but if we’re basically studying it as an artifact of culture. I think what’s different about a place like Gustavus and its particular Lutheran approach to religion is that it allows the possibility to say, “Various religions like various philosophical schools, or various ethical schools make claims about reality.

They make truth claims. And we do not ask that you accept any or all of them. But we’re going to take the claims they make seriously in the sense that we think that they might be good conversation partners,” right? That they offer ways of thinking about the world. They offer ways about thinking about what it means to be human. They offer ways of thinking about how people are supposed to live with each other. And they are good conversation partners to engage because these are traditions in many cases that have thought a lot about these questions over very long periods of time.

And they force us both to reckon with the places where our own thinking is pretty shallow and where we assume our own thinking is simply a given, and there’s no other way of seeing the world. So, that doesn’t mean you have to accept any of the answers. But we’re going to take religion as a place where you can ask really hard questions about the world and be in conversation with traditions that have thought long and hard about those questions, and have some answers with which you can engage.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s terrific. I mean, it’s exactly what we would say about in part, why study history? Why study anything, right? To be in conversation and debate with that. Yeah, great answer. Well, we have young people among us who are considering… among our listeners, considering Gustavus, be in touch with Professor Ruble and take her courses. You will learn a great deal. Sarah, this has just been a real treat for me. I’m so interested in your work. And we do need to team teach at some point. We got to work on that.

Sarah Ruble:

Absolutely. Yes, thank you. [crosstalk 00:56:27] the same room.

Greg Kaster:

Okay, yeah. Thanks so much for taking time out of your sabbatical too. That’s above and beyond. So, best of luck with that work, and take good care. I’ll see you back on campus at some point.

Sarah Ruble:

Absolutely. Thanks, Greg.

Greg Kaster:

All right. Bye-bye.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.