Gustavus English professor and poet Philip Bryant, Class of ’73, on his path from Chicago’s Southside to Gustavus, the impact of his undergraduate mentor, his experience as a black student on a virtually all-white small campus at the tail end of the long 1960s, the police killing of Mr. George Floyd, and poetry, including three of his own poems.

Season 3, Episode 1: “Poetry Is about Reimagining the World”

Transcript:

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of Gustavus Office of Marketing. Will Clark, senior communications studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast, and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

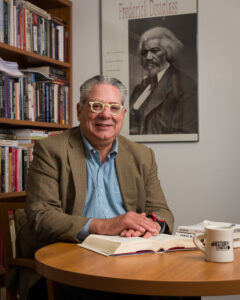

In a 2010 essay from Minnesota Public Radio, my colleague Philip Bryant, professor of English at Gustavus, reflected on his assimilation to Minnesota winters. “I’ve lived in St. Peter, Minnesota for more than two decades now,” Phil wrote, “and as a transplant from the South Side of Chicago, I don’t always fit in. But when it comes to the cold, I’ve become a truly naturalized Minnesotan. I still moan and fulminate about it, but I accept it as a fact of life here, just like everyone else.”

Phil joins me today to talk about both fitting in and not at Gustavus and in Minnesota, and also about his wonderful poetry. Phil graduated from Gustavus in 1973, and returned as professor of English in 1989, having earned his MFA at Columbia University. A popular and influential teacher, his courses cover such topics as the blues, reading and writing jazz, race and the American vision, Pan-African poetry, appreciating and writing poetry, and African-American literature.

An accomplished and admired poet, Phil has published four books of poetry to date, titled Blue Island, Sermon on a Perfect Spring Day, which was a finalist for the Minnesota Book Award in poetry, Stomping at the Grand Terrace, and most recently and my personal favorite, The Promised Land. Among his other distinctions, he has served on the governing board of the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis, and twice been a fellow of the Minnesota State Arts Board.

While the two of us have Gustavus and Chicago in common, Phil is the only one who can lay claim to being from the city, while as a south suburbs guy I can do so only indirectly through my dad, who grew up there. So Phil, I’m delighted to welcome you to the podcast.

Phil Bryant:

Thank you, I’m glad to be here.

Greg Kaster:

Great to have you. Let’s go back in time, and I guess back to Chicago, one of our favorite places, notwithstanding its flaws, and talk a little bit about your path from there to Gustavus. How did you come from the South Side to Gustavus? And I will confess by the way, I’m not even sure I’d ever heard of St. Olaf. Maybe Carleton, but growing up in the burbs I had not heard of Gustavus.

Phil Bryant:

Well, it was basically through one contact, a teacher of mine, who did about one year at my high school, and she was a Gustavus graduate. Her name was Anne Sullivan, and she was friends of Annie Martel, who was also the former ex-wife of John Denver. And Anne Sullivan taught at my high school, Chicago Vocational High School, and I met her there. She was an English teacher. And we were having a conversation, we kind of bonded, and we were having a conversation, and she asked me what I was going to do after I graduated, and I said I was probably going to get drafted and wind up in Vietnam.

And she said, “Well what about college?” and I said, “Well, my grades are kind of iffy on that, so I don’t know.” And she said, “Well I know this program at the college where I graduated, and would you be interested in applying or look in…” At that point just inquiring into it. And I said, “Sure. I mean anything’s better than the jungles of Vietnam.” I asked her where is Minnesota anyway? I remember we went to the school library and we got a big atlas out, and she actually pulled out a map of the United States and put her finger on St. Peter, Minnesota. And that was the first time that I had ever heard of St. Peter, Minnesota and Minnesota. I had a kind of vague idea of where Minnesota was.

And so that was my introduction, and then later on it just opened up from there. And I mean I can make this short, but it was just… I was able through her contacts to get connected into the DMOS program, which was basically one of the first prototype student at risk, affirmative action kind of program to bring non-traditional students to Gustavus, and Gustavus had got money for that, and they had a couple of sponsors from the board also, as I can remember it, to kind of fund it. So it was African-American students, poor white students, Native American students. I’m trying to think who else. But we were all kind of like at risk, you know, if I can use that kind of language.

And that’s how I got to Gustavus, and I know Rodney Davis was one of the prime movers and shakers of that. Also Bruce Gray and… I’m trying to think of who else was prominent in that. So anyway, there was about 40 kids in that program, and only two graduate from Gustavus, went through the four years. And it was me, and I’m trying to think of who else went through there. I can’t think. Boy, this is where your memory starts to go. But we were the two graduates of the DMOS program. It was Deferred Matriculation, something, Program, you know? So that’s how I got to Gustavus.

Greg Kaster:

That’s so interesting. I wonder if you were at the tail-end of an earlier effort by the college, about which I’ve learned more just recently, where President Edgar Carlson, who was really championing civil rights within the Lutheran Church, the Evangelical Lutheran Church, or whatever it was called then, had Bruce Gray, who was working at admissions, and Owen Sammelson in admissions-

Phil Bryant:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

… recruiting African-American students, both from the south and I think from Chicago. And then maybe the DMOS program was kind of built on top of that, or an outgrowth of that.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah, that’s exactly what it was. It was split level, because there was very aggressive recruitment, where Owen Sammelson and Bruce Gray went into the south, and they have some pretty interesting stories, because they would drive down there and go to these black high schools and recruit students out of there. There was a kind of channel, regular channel, those kinds of students, and they were more traditional than I was, and then the DMOS crew. And then the DMOS people were kind of again the at risk. We showed some kind of promise of being able to survive and matriculate into Gustavus. But it was really one of those very experimental programs back in the ’60s, where they were just taking students up and seeing if they could make it at Gustavus.

So there was a distinction between me and, say, the traditional students who were coming. Black students, I mean, who were coming up and being convinced to come to Gustavus. They had the grades, they had the SATs, they had those kinds of things that were backing them up. But they were still adventurous, in the sense that they were choosing to come way up north to attend this really small, all-white college in the middle of-

Greg Kaster:

Right. I mean, virtually all-white in all-white St. Peter in mostly all-white Minnesota, which is still the case, although the college and the state are so much more diverse than they used to be. What about that? How was it? I mean, you mentioned in that wonderful essay, which I could read only part of, about assimilation through Minnesota winters. What was it like for you to be a black student on that campus?

Phil Bryant:

Well, I kind of thought it as an adventure. It was very curious. I was curious about it. Only kind of reference I had to Minnesota were the twins and the Vikings, right? Because-

Greg Kaster:

[inaudible 00:09:13], yeah.

Phil Bryant:

… they played the White Socks and the Bears.

Greg Kaster:

The Bears, right.

Phil Bryant:

I didn’t have any other relationship with the state itself, and I was just lucky enough, really, to come to Gustavus and immediately come under the wing of John Rezmerski, who was a working poet, great poet, great teacher, and he became my mentor, and he was the one who opened up this burgeoning literary scene at… well it was at Gustavus but in Minnesota, because what John did was he just introduced me to all these poets and writers. Robert Bly, all these people that were his friends. And he would take his student, me, along and open me up to this literary scene. Now you see the Loft, you see… Minnesota’s at the center of the literary publishing world with Gray Wolf and other small, really important but national presses. And back in the ’60s, this stuff was just getting started. They were just basically these long-haired hippies and writer friends that John would introduce me to.

So that kind of kept me here. I mean, John… because I wanted to be a writer, so I was just soaking all this up. And John would take me to readings, he would take me up to the cities, and I would meet all these people, and I didn’t know who they were. And they were just John’s friends, and they were writing and they were publishing and they were talking about poetry. I mean, there was the classroom experience that I had, which was important, but more importantly I had this incredible resource, with this professor who was really willing to just take me almost as an equal. I was 18, 19 years old. I didn’t really know which way was up then.

And he was bringing me into this scene that would basically become the Minnesota writing scene that’s nationally known. I mean, writers all over the country come here because this is a place where you come if you want to get grants, if you want to get published, if you want to meet other writers. And that was just getting started. John was on the ground floor of that, and that was getting started, and all of his friends were part of that. And it was, again, a loose confederation, but it was still something that I don’t think you could duplicate in any other situation, in any other college, in any other school at that time.

So that was really important. That really set the template for me, in terms of surviving for years at Gustavus, because I knew I wanted to write, I knew I wanted to write poetry, but I wasn’t necessarily that clear in terms of how I was going to get there, and John really helped me in so many ways, in terms of filling and getting there as a writer, because it’s hard. This is not a country or society that necessarily supports or nurtures writers, so when you get a situation like I got at Gustavus, that was gift from god, you know?

Greg Kaster:

Had you been writing anything, poetry or essays before hooking up with Rezmerski?

Phil Bryant:

Yeah. I mean, okay, I’ll give you… when I came to Gustavus on the DMOS program, we came two weeks early, because it was kind of like they were going to try to dip us into the water gradually before… So I was here in August, and staying at Fred and Janet Brown’s house, which is right about three doors down from where I live now. And Fred Brown was this incredible history teacher, and he was also dean of the school. He became president of Doane College out in… I think it was Nebraska somewhere. But anyway, I was staying at Fred’s, and Fred came to me one morning, we were having breakfast, and he says, “I want you to meet this guy from the English department, John Rezmerski, and he’s a poet.”

And he asked me if I had any work. Well, I just bought everything I had written in high school, stuck it in my suitcase and brought it along with me. I said, “Oh yeah, I’ve got work here.” So John came by later on that morning, and I just handed him all of my work, and John says… I don’t remember this. I didn’t think I had that many poems. But he said that he read close to 300 poems that I had written in high school.

Greg Kaster:

Wow.

Phil Bryant:

And I mean, none of that stuff survived. I don’t know where that is. But he went, and it took him like two hours. He said, “Well just go and do something, and I’m just going to sit here,” and he went through every single one of my poems, and that was my first meeting with him. And after two hours we had a discussion, we talked about it, but that was kind of the beginning of it. For John, I mean our relationship started… I mean, I was in a lot of his classes, but there was this kind of… He pulled me under his wing, and he showed me the ropes on how I was going to do this. He saw that I was writing all the time, but I was also interested in being a rock musician too. I mean, I’m no good, but that was one of my interests too. And there was a political thing going on, so there was a lot of stuff going on.

And John’s presence and his mentorship and his teaching really focused me in terms of the essential things that I had to do to become a writer. And you saw that. I mean, my handwriting was bad, my spelling was atrocious. I don’t know if I should tell my… students will hear this. But I say, “Man, if I can pick out your misspellings, that’s really bad, because I’m real dyslexic.” But now we’ve got spell check, right, so it doesn’t matter.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Phil Bryant:

Nobody out here’s a black kid coming to… and this sketchy DMOS thing. Shouldn’t really be in college because he doesn’t really show any kind of… on record, any kind of academic wherewithal to get through a program. So again, that was a godsend to have him here. And I was really afraid of him because when John came to Fred’s house, his hair was… he had this crew cut, and John was working-class, so he had this crew cut and this button down short sleeve shirt and khaki pants, so he looked like somebody in Chicago, that I would run away from. We won’t get into the violent racial politics of that. So I looked at him with my eyes, “Oh my god,” and he turned out to be the sweetest, most tender-hearted, most generous teacher that I ever had.

And I told John that later on, he just laughed at it. He knew where I was coming from, because he’s from the working-class, and he grew up in that same kind of milieu, where you have those kind of racial divisions. So he kind of understood my trepidation when I first saw him. I mean, in the flesh. It was like oh my god, he’s a greaser. That’s what we used to call white dudes. Man, he’s a teacher. He teaches here?

Greg Kaster:

That is such a great story, and as you said earlier, of course some of this happens at any college or university, but it’s really special. I didn’t attend a liberal arts college. My wife, Kate, did, who taught history at the college. But I’ve learned teaching at Gustavus over the years it really is a part of the liberal arts ethos. Those kinds of relationships that you build with students. And it can go in some wonderful directions, both in class and outside of class. What about socially, what was it like at that time for African-American students at Gustavus? Was the pan-African student organization or black studies, a black student organization in existence? Was there much interaction between white students and black students? What do you recall?

Phil Bryant:

Okay, so here’s what the deal was, and hopefully I can get the timeline straight on this. The spring before I came in… I came in in the fall of 1969. In the spring of ’69, and John tells me this story, they had Haki Madhubuti, Don L. Lee, come and give a reading at Gustavus. He gave a screen reading. And Don L. Lee was a cultural nationalist. Black nationalist. And he had his famous book A Screen Don’t Cry. And I knew about Don L. Lee, because Don L. Lee kind of lived in my neighborhood. I’d see him driving around in his little yellow Volkswagen. And there was also Third World Press, which was Dudley Randall. That was right down the street from where I grew up. That was on 75th and Cottage Grove. So there was a burgeoning literary scene in Chicago under the auspices of Gwendoline Brooks, who was kind of mentoring and supporting and affirming these young writers like Don L. Lee, Haki Madhubuti.

So Don L. Lee was doing the college tour, came up to Gustavus, just blew everybody away. Told the black students they should really take seriously their blackness and really think about what they could do with the black student organization and all of this. So he basically radicalized the black student body at that time, which beforehand they were kind of sleepy. It was kind of like… I’m going to say usually is. But there wasn’t that much ferment or protest or presence, and then after he left, I mean everybody started getting Afros, everybody started taking things seriously.

So that’s where I came in in ’69. That was really the beginning of I would say the militant period of the BSO, where people were very influenced by black cultural nationalism, solidarity with blackness, and also the black table came into being that year, where white students were not particularly encouraged to sit at this table. That was the black table. Everybody knew in the school that this was where black people sat, and you maybe stepped over the bounds if you were white and you just decided to sit there, right, in that way.

Greg Kaster:

[crosstalk 00:21:46].

Phil Bryant:

Yeah, that was kind of the atmosphere when I came in 1969.

Greg Kaster:

[crosstalk 00:21:53].

Phil Bryant:

It was very political, yeah.

Greg Kaster:

And that table was in the cafeteria, right?

Phil Bryant:

Oh yeah, it was at the south end of the cafeteria. They kind of moved around. I think it was more towards the center, and then towards the south end, where you go in the main entrance, and there was like about… it was about two tables across, and just solidly, that’s where black students sat, yeah, to eat. And even if it was empty, nobody sat there, if they were white.

Greg Kaster:

Did you find yourself hanging out with any or many, a few, white students, or what were you-

Phil Bryant:

Oh yeah, yeah. I mean, I was kind of a hippy then. That caused a little bit of tension, because everybody’s having kind of like this political consciousness thing, and blackness was… this was the beginning of the latter part of the ’60s, so yeah, I would kind of sit there, but then I would sit with my white friends too. I mean, I was kind of floating back and forth, which drew criticism, but hey ho. I mean, it’s water under the bridge, but that was… yeah, I was nominally… People kicked me out of the club because you’re in this club for life. But there were some discussions in terms of my reliability in terms of the revolution.

Greg Kaster:

Oh man.

Phil Bryant:

Over [inaudible 00:23:50] all these white friends and associates, you know? But again, it’s water under the bridge too as well.

Greg Kaster:

That’s all great. The historian in me wishes I could have been there. Back to poetry. We talked about you reading a little bit, which we’ll get to shortly. Can you say a little bit more about what is it that attracts you personally to poetry, because that’s mostly what you write. I mean, you’ve written some essays which are also wonderful, but poetry is really your main gig.

Phil Bryant:

Okay. Without trying to sound too chauvinistic, I think poetry is the most difficult… I think it’s really difficult to write well, and Pound was right when he… I think it’s in the ABCs of Reading and Writing, it’s this little booklet he wrote back at the earliest 20th century. Really kind of defined modernism, and he said you can find essential elements in good prose and good poetry, so he didn’t make a distinction between prose and poetry. And that’s true, it’s hard to write good prose and poetry. But poetry, to me it’s the hardest to write, because of the incredible amount of concentration that it takes to do it. If you’re just writing 18 lines or if you’re writing a sonnet, 14 lines or whatever, I mean that’s incredibly difficult to write just a good poem.

And that was always kind of like a challenge for me, in that way. And something that even in high school I realized when I was attempting to do it, that I would probably spend most of my life trying to write a decent poem, or two or three if I could. So the challenge was there, and also just the fact that with poetry it’s about expressing feelings and emotions that people, when they read the poem, they can pick it up. Maybe not in the same way that you’re feeling them as you’re writing, but just they can pick that up. And that’s very akin to music, where music… I love jazz. I love all kinds of music, but jazz, where you hear a solo by Ben Webster or Don Bias or Lester Young, and they’re masters at their form, but yet their mastery goes beyond the fact that they’re just playing this incredibly difficult music, but it’s also they’re playing the feeling and the emotion within the music. Their notes are able to embody that.

And that’s something that to me is about poetry. Poetry is about feeling, it’s about sound, it’s about sense. It’s very visceral. It’s body-linked. So all those things, yeah. A lot of my work has dealt with music and [crosstalk 00:27:23]-

Greg Kaster:

[crosstalk 00:27:23]-

Phil Bryant:

So that’s the connection, yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I was going to ask you about that, the music connection, because as you just said, a lot of your poetry does deal with music. I think the first poem I heard you read might have been my first year at Gustavus… I loved it. It was about jazz or the blues, I remember that much, and thought it was fantastic. But is that a combination? And by the way, is one of your poems or one of your collections kind of a jazz-

Phil Bryant:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

With music, right? Jazz memoir [crosstalk 00:27:58]-

Phil Bryant:

Yeah, that’s Stomping at the Grand Terrace

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, yeah.

Phil Bryant:

Dedicated to my father, and my father was like this incredible aficionado if I can use that Hemingway term, of jazz music. I mean, he grew up in the depression and kind of reached young adulthood in the ’40s, just when the bebop revolution. So he was very influenced by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, and he saw these people live. And Chicago is… I call it like Leipzig or Vienna of musically… it’s really an important center for jazz and for blues and for gospel. I mean, just black music. I didn’t know. I mean, I grew up in this kind of vortex of creativity on the South Side, and it was just within blocks of where I grew up. It was like in the air you breathe. I did take it for granted that this… oh yeah, this is just the way that it is.

But yeah, that’s my connection. I think that’s my connection with African-American culture. I feel that the music is really the weight-bearing beam of African-American culture. I mean, that’s a whole nother conversation of why that is. It comes out of slavery. So everything has to be packed into the music. The whole sense and sensibility, the religion, the spirituality, the history, the experience, everything has to be packed into that. And it has. So it operates in that way, where you’re connected. I mean, you can actually hear the music and it connects you right back to the slave quarters, where really feel extant American culture sprung from. I would say 95% of it goes through the slave quarters, and-

Greg Kaster:

We are an African-American culture as much as, maybe more, as a European culture as-

Phil Bryant:

Oh totally, totally, yeah. Our sensibility, our orientation comes out of the history of slavery, and what the slaves, in order to maintain their own… or enslaved people. To create their humanity, they had to do that in ways that were going to be sustainable to them in the long haul, and this music kind of arose out of it. And it really is the crucible of American democracy, because it totally… it roots itself in that, but it also reflects that in this aspirational point. But it’s also deeply, deeply spiritual too. It really is about exploring the soul of things, and it expresses itself in that form too as well. Yeah, I think it’s the most important thing that… out of this kind of tragedy empire that we seem to find ourselves in, and it really kind of speaks of its redemption or possible redemption. So that’s what I feel the music is very, very essential for that. And not just for me, but I think for every single American, you know?

Greg Kaster:

I love that. African-American music is the weight-bearing beam of African-American culture, I think that’s so true and so well-put. How about some poetry?

Phil Bryant:

Oh yeah, okay. So-

Greg Kaster:

Tell us what you’re going to read, please.

Phil Bryant:

I’ll read three little short ones. Since I’m kind of an erstwhile sports fan, I’m trying to wean myself off the NFL. But I haven’t successfully done that. Maybe 80%. But for all the things that were going on, but also I’m really heartened to see players speaking up. I mean, it’s just incredible to hear players, former players speaking up. So you’re getting these really articulate voices coming out now and speaking and maybe having an effect on things. In The Promised Land, I have this little short poem that I dedicated it to Colin Kaepernick.

Greg Kaster:

[inaudible 00:32:45] poem, thank you.

Phil Bryant:

Thus Knelt Colin. I don’t know if people know it, but Thus Knelt Colin is kind of a little bit of a play on Thus Begs Zarathustra. So I’m thinking about that, speaking Zarathustra, and then here Colin is kneeling. So anyway, Thus Knelt Colin. And on the far, far sidelines, during our national anthem, thus knelt Colin. Head bowed down to the ground, as if in some deep silent mournful prayer. Long before anybody noticed him, and long before anybody else dared. So I kind of saw that as a prayer that he was doing, rather than just simply kneeling protest. He was praying for redemption of our country, of our democracy, with the flag there, and it’s like totally misinterpreted, of course, in that way.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Phil Bryant:

But that’s how I saw it, because he wasn’t really making it a public gesture, as public a gesture as it became. Some sports writer saw him and thought he was injured at first and was going over and saying, “Are you okay? Why are you…” And then Colin told him why he was kneeling, and that’s how it got out. But he had been doing it for a little bit before that, nobody really noticed it til that sports, I think it was an ESPN guy, noticed it. “Oh man, is Kaepernick injured? He’s sitting there on the bench or whatever.” Because he was kind of sitting down, so he was trying to scoop a story, he was trying to get a story from that. That’s how that came out.

Greg Kaster:

You’re right, it’s very… When you think of that now iconic image of him kneeling, head down, I mean it’s public in that he’s doing it in public, but it’s also very private, very personal.

Phil Bryant:

Yes, yes. It’s very-

Greg Kaster:

[crosstalk 00:34:57] more powerful, I think.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah. So that’s what I was-

Greg Kaster:

Go ahead.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah, yeah. I’ll read-

Greg Kaster:

Did you [crosstalk 00:35:04] this to him at all, or have you shared it with him, the poem?

Phil Bryant:

Oh, uh-uh. I just kind of wrote it and just kind of put it in the book when we were putting the book together, because it was… Yeah, it’s kind of political, and I was trying to balance the book. I mean, I took a lot of poems out also that were more political. So I wanted it to hit in a certain way. So this one I felt strong enough about to say, “Okay, maybe people will start to reimagine his kneeling in a different way,” and I think that’s what I was trying to get with that poem, because poetry is about re-imagining a world into… not into fantasy kind of thing, but into how it really is. What is his kneeling really about? I mean, it’s obvious now after George Floyd, right?

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Phil Bryant:

What it’s about. But then people were kind of… is it about the flag? Is it about disrespect? No, it’s about prayer. It’s about prayer for this country that is not at all aspiring to what its true principles should be and what that should be. That’s what I was trying to get people to look at.

Greg Kaster:

[inaudible 00:36:36] example of… I mean, I know you’re going to read a couple more. That’s an example of a poem-

Phil Bryant:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Of one poem being inspired by quote, unquote current events.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Go ahead, please. More.

Phil Bryant:

Okay. I’m going to read this little short one called Bell Ringer, and it’s a little bit cryptic, but I think it comes through. Okay, so Bell Ringer. Black lives matter, as all lives should matter, you could say. Both are just different parts of the same thing. Yet a bell will always need a bell ringer, you know, in order to ring.

Greg Kaster:

Fantastic. Obviously you wrote that before all the recent [crosstalk 00:37:33]?

Phil Bryant:

Oh yeah, this was way… I’ve always been a big fan of Black Lives Matter, because it’s a kind of millennial thing, and I’m old now. What I really appreciated about them was their openness, their fluidity. They’re fluid, they don’t have one spokesman, they don’t really have an organization. It’s really totally kind of grassroots. And it was kind of taking a lot of things from the earliest civil rights movement, nonviolence but confrontation, and that kind of thing. And I heard people badmouthing them. It’s like how can you badmouth Black Lives Matter? These people are like heroes. They’re kind of taking the mantle from the early civil rights movement in Selma and Montgomery and all those other places, and they’re updating. I mean, they’ve totally updated it.

So I thought about that poem in terms of kind of just giving them my little small affirmative… whatever matters. My own thing to them. But also thinking about that bell ringing. Yeah, you could say all lives matter, but black lives matter, and this is the bell. The bell that kind of sounds this… When you say something like that, it is about everybody’s freedom when you say black lives matter. You don’t have to say all lives matter. That’s not the point. I was trying to get that relationship with the image of the bell and the phrase black lives matter, and it kind of works. I think it does, you know?

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. I think for me, hearing it, and reading it and also hearing it… the first time I’ve heard you read it in the aftermath of Mr. Floyd, George Floyd’s murder, here in Minneapolis. I mean, in a way that event is a bell ringer too.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

We should say something about the title of the book, The Promised Land.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Greg Kaster:

That history is so important. Go ahead.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah, I mean it’s basically a book about the great black migration, which was the largest internal migration in the history of this country, where you had millions of African-Americans around the early part of the 20th century… probably before, but really started picking up during World War One, where you have that migration from the south to the north. And so right up until World War Two, and even after World War Two, you had the largest segment of the population of African-Americans in the deep south, and then after World War Two it was just almost like a flip. So you had… the largest population was in the north, and the northern cities, also western cities like LA, but Chicago, Cleveland, New York, Philadelphia.

So that was part of it, but also I was kind of thinking about Martin Luther King’s last speech that he gave before he was murdered. And he said he had gone to the mountaintop and he had seen the promised land, and the title poem of the book kind of deals with that, that speech, and that was such a haunting speech. He was kind of processing his own mortality, which was just 48 hours away. And so that promised land, and where is that promised land and will we as a people ever get to the promised land? King said, “I’m here to tell you that you as a people will get to the promised land,” and that’s the open question about American democracy, about really the soul of the country, is about this promised land, because it’s not only a physical material thing, but it’s deeply, deeply spiritual.

King was a preacher. He was coming out of a southern Baptist church in that whole tradition, so all of that was speaking in terms of the spiritual journey that he was on and that civil rights people were on, and that the country was on. The country’s on a very spiritual journey, and that set the core of it. Will we reach the promised land? Will we reach that realization of democracy that we need? And of course, democracy is not just in terms of politics, but it is also the spiritual aspects of democracy that was first spoken of by Walt Whitman and Lizo Grass, when Lizo Grass came in. There was a spiritual testament, poetic and spiritual testament, about the possibilities of a democracy and a democratic culture, a democratic society. So all of that kind of is embodied in the poetry, and that’s… again, I just named a few sources. Whitman and King, history of the great migration, which my family was a part of, moving up from Tennessee to Chicago, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Greg Kaster:

And memorialized in the great art of Jacob Lawrence. Is that a Jacob Lawrence on the cover?

Phil Bryant:

It’s actually an interpretation of another African-American artist. His name is Alan Forest, and he did… I was going to try to get the Lawrence thing, we didn’t know how much it was going to cost, but I came across this just on the internet, searching on the internet. I just love this. It’s kind of like a crayon of these people packing up and leaving. And so my publisher just got in touch with the artist himself and asked if we could use it. He said yeah, so that was really wonderful that he gave us permission right away to use it, because I just really love his painting of it. It was really kind of like… I wouldn’t say charcoal, but kind of crayon charcoal color of this. There’s so much movement. The movement, that’s the whole point of it, in terms of movement towards this promised land.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I love that cover, and I also… I love your poetry, all of it, especially the music poetry, but this one particular because it resonates with so much history. I’m drawn to it, just the promised land collection. One more, please.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah, I was going to also read this one last poem that I wrote called Smile, and this is a St. Peter poem, with some St. Peter street names and numbers on it. And I wrote it for Alex Pates, who’s an African-American writer. Did a book called Amistad, which was based off of the movie about Amistad and Cinque and… Who was it? I think it was John Adams.

Greg Kaster:

Quincy Adams, yeah.

Phil Bryant:

Quincy Adams, yeah. An so he started this program that’s still going on, called the Innocence Program, where he’s trying to sensitize educators to African-American children. This has to do with the internal bias and how African-American students, young kids, are perceived and also treated in the schools, and it’s almost trying to recapture innocence, because we lose innocence very young. I mean, African-American males, and I say girls and boys, where we’re not treated or accorded our childhood innocence. I mean, we’re treated as if… well, that’s another conversation, but in regards to that, nobody’s trying to protect us. Nobody’s trying to nurture us in any kind of way. So Pates’ Innocence Program is about making teachers, primary, grammar school teachers, sensitive to that, and it’s part of their internal bias, you know?

Like we get sent up to the detention rooms, like just percentage-wise a lot more. We get harsher punishments. We aren’t given instruction, we aren’t given any kind of encouragement young, because people have already kind of pegged us… well they’re candidates for the penal system or the correctional system, so why bother doing that? So that was the poem’s idea, was about that, to kind of… the poem’s… I wouldn’t say idea, but just the center of the poem.

So Smile. They’re just across Madison and Third Street. Recently arrived immigrants. A young mother and her two children, a girl and a boy, with tight rung curls of jet-black hair, like sparse patches of thick shrubbery, on some arid desert plain. I look at them and smile. A girl with curly spools of black hair looks back at me and smiles. And I think of all those thousands of miles they had to travel to come here to this very cold and often lonely godforsaken place, where the deep brown of his round face can easily break into a great big smile, all the way from Somalia, east Africa. A true smile, just for me, and for all those who pass by him now. Don’t even look, or maybe choose not to see.

Greg Kaster:

Fantastic. My gosh, that just makes me think about all the ways in which Minnesota, with all due respect to Garrison Keillor, is not just Scandinavian, especially today with all the rich immigration from Africa, from Latin America, from Asia. I love that, that’s beautiful.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah. That’s kind of based on… I do bike rides around St. Peter, and I just saw this family. It was a mother and her kids and I slowed down, and was I was going by, I caught this kid’s eye, and he just smiled at me, and I just smiled back at him, and that’s Alex’s point, is that these kids need affirmation, they need our support. They need even just acknowledgement, recognition, they’re not invisible, they’re here, and they should be welcomed and connected as part of the community, as part of who we are as American people. So his smile kind of inspired me to write that, and Alex is a program too as well.

Greg Kaster:

Wonderful program and poem. I almost hate to bring this up after that poem, but it relates. What about the murder of Mr Floyd, George Floyd, by Minneapolis police? First of all, just I’m curious about your personal reactions then and since, but also whether you imagine any poetry coming out of that particular event?

Phil Bryant:

Well, to me it’s kind of like this racial groundhog day after Bill Murray’s movie. We keep doing the same dance, and people are dying, you know? And can we get off of this and get on to something else? It was just a great sadness that came over me, personally, because it wasn’t surprising at all. I myself have been in situations that [inaudible 00:51:25] the way that his went, but it could have. It could have. And there’s so many other people, African-American people, who can tell you stories like that. I mean, I’m here talking to you right now, because it went one way and didn’t go another. It could’ve gone another way, and so I wouldn’t be here talking to you. It had the potential.

And so, I think hopefully people who didn’t quite believe it, or they always think… I mean, this comes out of the racial mythology of America, where African-Americans say these things, have been saying these things for hundreds of years, and people just think we’re exaggerating, you know? Like, “Oh, just African-Americans, they exaggerate this. That can’t be true,” right? And so that was a moment, for whatever moment… it was kind of like LA ’92 again, where you had that beating. The LA Police Department, and the guy was videotaping it. And here you have another situation. And you have so many other videotape out there. The quantity of them, the summation, culminating, that it hit, that people finally… “Oh, these people aren’t exaggerating.”

And this has been going on for a long time, and it’s systemic. It’s built in to the very fabric of policing, police force, that you can… You’re a historian, right? You can take all the way back to slavery, and the slave patrol and let me see your papers and where are you going and who’s your master. All of that is at the root of modern policing in America.

Greg Kaster:

Policing the black male body, in particular.

Phil Bryant:

Yes, yeah.

Greg Kaster:

[inaudible 00:53:32] the female body, in other words. Yeah, no, absolutely true. It’s funny you mentioned the groundhog day. That’s actually a movie I both like and hate at the same time. I mean, again, my first reaction was, “Really?” I just yelled, I screamed, I was angry, but also… really? Thinking of Eric Garner, especially. It does make one wonder how far away is the promised land? On the other hand, to end on an upbeat note, before we were recording, you had mentioned how your sense that the protests in response to Mr Floyd’s murder are different and perhaps more hopeful than let’s say in the 1960s.

Phil Bryant:

Well, what I’m hopeful about is the fact that even though we’re just really in a crisis situation, this could completely unravel and the wheels are already coming off, but that said, I think the younger generation is actually benefiting from the water that has already gone under the bridge. So they don’t have to necessarily retrace those steps again. They can move on. I mean, they have enough challenges ahead of them anyway, and so their ability to kind of unify and to link themselves, in a multiracial way, multicultural way, they have much easier routes and avenues to that than we did in the ’60s. I think it was much more difficult in the ’60s to have those broad, multiracial, multicultural connections. Not to say that it’s a panacea, but this is something that I’ve observed. It seems like it’s kind of second nature. I mean, I don’t know if you read the book White Fragility. I don’t know, I’m-

Greg Kaster:

Yes, yes.

Phil Bryant:

This is where I really disagree with the author. What’s her name, DiAngelo?

Greg Kaster:

I can’t remember her name, but I know the book. I have the book, yeah.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah. She’s right to the certain extent, she’s like, “Well youth have… they’re just as racist as old people are.” And I would say yes and no. I think that you have to understand that history has moved. We have moved in time. And these kids are… I like to use the term… they’re not as hysterical about race and sex as we were when we were their age, and that in a lot of ways they’re more sanguine and they’re more open to listening to things that really kind of contradict or counter their own background, and challenge it.

And again, and there’s a lot of kids that aren’t about that, they’re like neo-Nazis or skinheads or alt-righters or whatever. But there are a lot of kids who are just… they’re open to the messages that come from the other side of the racial divide, and they’re able to look at those messages, look at that information very different from the way that my contemporaries back in the ’60s were processing it. And there were a lot of things that had to be… they just have the benefit of a broader, larger, deeper American narrative, and they just grew up with that. They grew up with the presence of black culture, black music, black people being central to their life. And they’re just trying to dice all that in respect to well this has been so central… I mean, these people are central to who I am as an American, but yet still this is a white supremacist country.

And the two things don’t go together. And this is where you’re getting these kind of demonstrations in this way, and I think both black and white young people are saying that this is a complete disconnect in the way that they… Those conclusions couldn’t have come in the 1960s. Yeah, I think it was impossible for our generation, my generation, to really come to the same kind of conclusions.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Like you, I find it hopeful. Looking around [inaudible 00:58:34] I live here downtown, where I am now, and seeing some of… in Minneapolis, the protests and the mix of… I mean, all different backgrounds, colors, you name it. And also at the memorial, the murder memorial/memorial site, the same thing. So like you, I find that hopeful, and I think you’ve articulated quite well why that is the case, what’s happened. And I agree with your criticism of the book, White Fragility, that I think misses that or underplays that important change.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Phil, I could keep talking to you forever. I love talking to you, and not just because we’re both from Chicago.

Phil Bryant:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Your poetry, the way it lends music, history, politics, the personal, I mean everything, is terrific. People who are listening, run right out and buy… well buy all four collections, and any prospective students listening, make sure you get to Gustavus and take some courses with Professor Bryant. You will not regret it. Take good care, I hope we can talk in person soon back on campus.

Phil Bryant:

All right, Greg, and thank you. And take history courses too.

Greg Kaster:

[inaudible 00:59:47] thanks a lot. All right, take care, Phil. Thank you, bye bye.

Phil Bryant:

Bye bye.

Leave a Reply