Soil is a universe—alive and brimming with life and potential just now being discovered. Incredible science is happening within the world just beneath our feet, and this year’s Nobel Conference presenters have dug deep. Here’s what they’re learning.

The Earth Microbiome Project

Jack Gilbert, director of the project and microbiologist

Founded in 2010, the Earth Microbiome Project is a huge crowd-sourced effort to document microbial life, much of which can be found in soil. “It was designed to generate data to help us characterize the bacteria and archaea living on our planet,” says Jack Gilbert, director of the project and a presenter at this year’s Nobel Conference. The idea was to understand microbial communities from their own perspective.

It was executed in a methodology that fosters open, collaborative science and data sharing. “We wanted to work with the entire scientific community to understand what we’ve got,” Gilbert says. All told, more than 500 collaborators from 43 countries collected 27,751 samples from organisms and environments—from the human gut and a bird’s mouth, from the soil of an Antarctic volcano and a river in Alaska, and from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

The team behind the EMP then analyzed and categorized approximately 200,000 samples from these communities. The result: a global Gene Atlas—a microbial map that is the world’s first reference database of the bacteria that colonize our planet. It’s a shared resource that researchers can now use to identify, study, and interpret trends and patterns in ecology across biomes and habitats, including the life and processes of soils.

“Based on that first survey, we estimate there are about a trillion bacteria and archaea,” says Gilbert. Now, the project has broadened to include metabolites and genes. And there’s a spinoff project—the American Gut Project—also the result of crowd-sourced samples and citizen science.

“The Mother Tree”

Suzanne Simard, professor and ecologist

Suzanne Simard’s popular Ted Talk contains startling science that seems like fiction. Through her research, we now know that forest soil contains a biological pathway that allows the forest to behave as a single organism and trees to communicate.

Literally, trees talk to each other.

Simard, professor of forest ecology at the University of British Columbia who will present at this year’s Nobel Conference, discovered that trees exchange information through mycorrhizal networks—webs of fungal threads in forest soil so dense there can be 60 miles of it under one footstep. It’s like the Internet, complete with hubs: In a single forest, a “mother tree” can be connected to hundreds of other trees. That mother tree sends excess carbon to seedlings, recognizes her own kin, and adjusts the sending of nutrients according to conditions and needs.

There is danger to forests when we take out mother trees—like any family, a forest is weakened when its mother is lost. But mycorrhizal networks do repair rapidly, and forests, Simard has discovered, have an enormous capacity to heal themselves.

Carbon Sequestration

Claire Chenu, special ambassador to the United Nations on soil

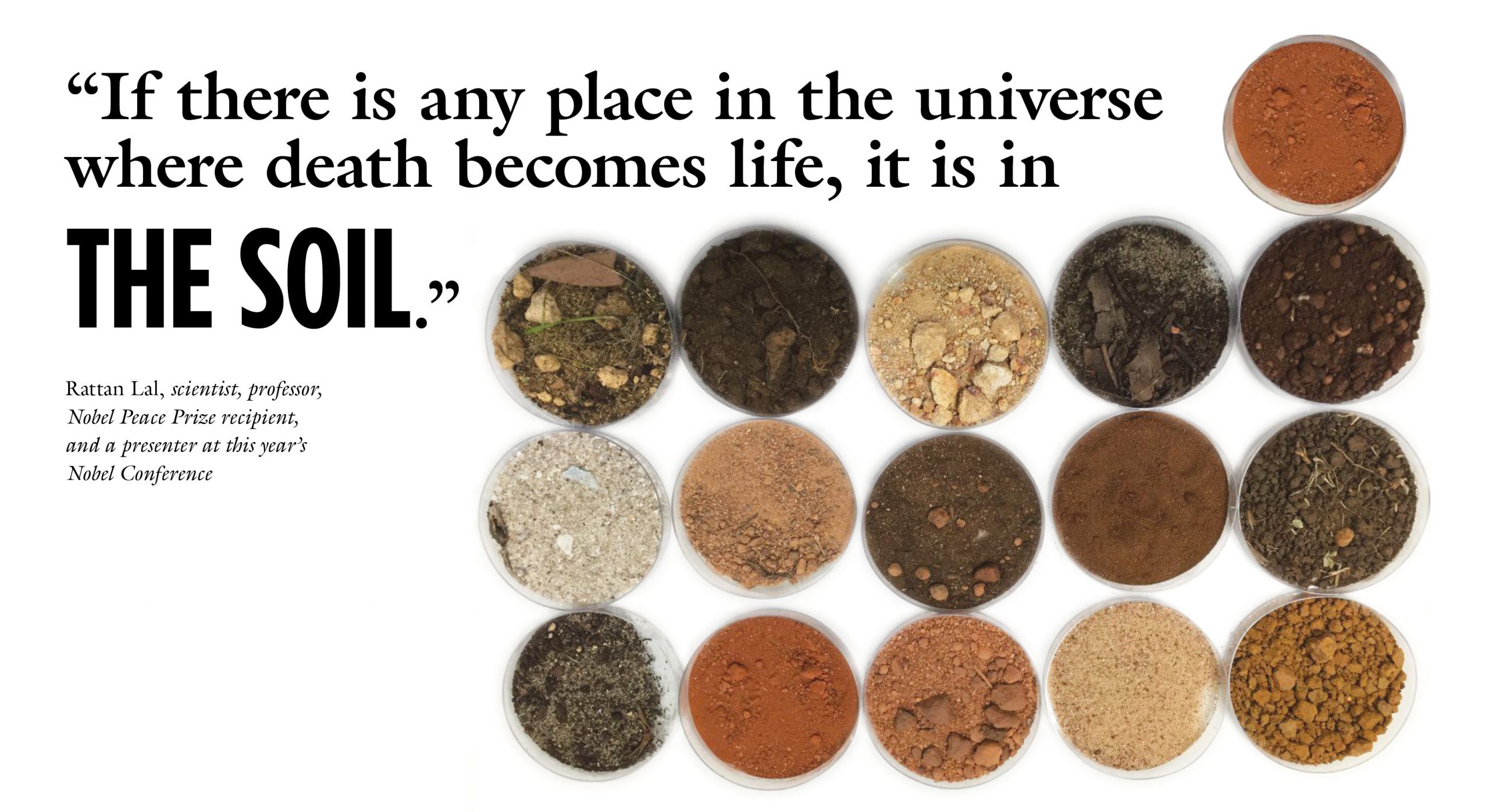

Rattan Lal, scientist, professor, and Nobel Peace Prize recipient

A key to slowing global warming lies quietly waiting under your feet.

Through photosynthesis, plants take in carbon dioxide and give off oxygen. When plants winter or die, part of the carbon is preserved in the soil. Since the advent of modern farming, soils have lost 50 to 70 percent of their carbon. Yet research has shown that no-till agricultural methods and crop rotation, as well as cover crops or mulch, preserve and increase carbon amounts in soil without decreasing crop yield.

Sequester that carbon in soil and you offset greenhouse gas emissions, enrich the soil, and grow more nutritious crops.

There is already carbon in the soil. “Soil contains our largest terrestrial carbon pool,” says professor Claire Chenu, a presenter at this year’s Nobel Conference. This is what she told the United Nations in 2015, when she was Special Ambassador for the International Year of Soils.

The more than 570 million farms in the world are not the enemy. “Agriculture is actually a solution,” says scientist, professor, and Nobel Peace Prize recipient (and conference presenter) Rattan Lal. “Climate change cannot be solved without agriculture at the table.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.