Kathy Lund Dean, Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Leadership and Ethics at Gustavus, talks about her education and research in management and ethics, ethics and academe, religious discrimination disputes in the workplace, corporate sustainability, and the case for studying economics and management at a liberal arts college.

Season 5, Episode 4: The Business Imperative for Doing Right

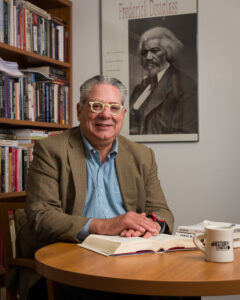

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of Gustavus Office of Marketing. Will Clark, senior communications studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast, and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

Business administration and French, management and ethics. Well, these two pairings might strike some as incongruous and in the second case, even antithetical, they’re in fact the undergraduate and graduate subject areas pursued by my esteemed colleague, Professor Kathy Lund Dean of the economics and management department at Gustavus. Kathy received her BA in business administration and French from the University of Notre Dame, her master of management from Aquinas College, and her PhD in management and ethics from St. Louis University. Since 2012, she has been the Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Leadership and Ethics at Gustavus, which among other responsibilities has involved her in building the college’s brand abroad, and growing experiential learning amongst Gustavus faculty and students.

In addition to teaching courses in management and business ethics, Dr. Lund Dean is a leading scholar and much sought after speaker in those areas with a distinguished research record including long lists of journal articles, conference presentations and invited talks, as well as two recently co-authored books, titled respectively; The Ethical Professor, and course design and assessment in Engaged Learning. She’s the recipient of numerous honors and awards, including two Erskine Fellowships from New Zealand, which funded her teaching there at the University of Canterbury.

I’ve been eager to speak with Kathy on the podcast about our research into ethics and professors, and also of particular interest to me, are religious discrimination disputes in organizations and their resolution. Plus, I always enjoy talking with a fellow Chicagolander. So welcome, Kathy. I’m so glad we could finally do this.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Greg, it is great to be here, and I’m so excited you’re doing these podcasts.

Greg Kaster:

Thanks. It’s really been fun. I know, it’s like any place. I suppose any organization, we do some water cooler talk now and then, or on committees. But the chance to actually talk for a sustained time about your work is what makes it so much fun. And not just your work, your background as well. Let’s start there. Let’s start with, so you’re like me, you grew up in Chicago or Chicagoland. But tell us a little bit? I grew up in Park Forest, I grew up in a different Park.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

But I grew up in Park Forest, so mostly in the south suburbs. Tell us a little bit about where you grew up and how you came to Notre Dame and how you came to be interested in both Business Administration and French.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Well, you’re a South sider, I am a North sider. So we should technically not be speaking together. But I grew up near the Skokie area in Evanston. Most people know where that is. And went to the same high school, Maine East High School that Hillary Rodham Clinton and Harrison Ford went to, Those are our famous alumni from my high school.

Greg Kaster:

Nice.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And it was a huge and diverse school. And that has been really instructive in I think, the way now I see the world. And I realize now the world that I grew up in was sort of an early version of some of the issues that we’re facing now as a culture in our country. And so, the conversations around diversity and otherness and things. In some ways, they don’t make a lot of sense because that’s the way it’s always been in my world.

So I grew up there, I have an older sister, who also went to Maine East. Notre Dame was sort of a random choice, in that we had, I remember just one of those big college recruitment things in our gym. And walking around and the recruiters at Notre Dame just looked and said, “Hey, you look like you want to go to Notre Dame, right?” It was that random and just talking with them. It was the right size school for me. I liked very much the religious tradition at that point, and the rigor of it, and just the campus. If you go to the campus, you’ll never leave because it’s a truly lovely place.

Greg Kaster:

I’ve been there just once, yeah.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And so, that was a really interesting place to go. And I really also enjoyed the chance to take advantage of a liberal arts place because ultimately, Notre Dame is a liberal arts institution. And so, the French major along with the business major was a really nice way of combining what they did well in my absolute love of language, and the ability to go into a business environment right after school.

Greg Kaster:

Where did the love of language come from? Did you already have that from Notre Dame?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah. My sister who’s four years older than I, she started speaking French. And our high school had this unbelievably skilled French teacher, who still hold the leadership position in Alliance Française in Chicago, Madame Steinhart, and she just built this great program. And we both are fortunate where language comes pretty easily to us, we can hear it pretty well. And just really I think learning another language is, in some ways a go no go thing like you have a competency and you love it, or you have to work much harder at it. And we were fortunate that we could hear it and we spoke it a lot together. And it was really a nice source of connection between us.

Greg Kaster:

That’s great. You can speak it behind your parents back then.

Kathy Lund Dean:

I know, right. And we used to just really frustrate them. It was great. What else does a high school kid do other than sort of annoy their parents?

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. You mentioned the religious tradition appeal to you? Or was that part of your upbringing? Did you grow up Catholic? Or was that just …

Kathy Lund Dean:

Well, my dad was Catholic. And we had a lot of friends that were Catholic that went to Catholic school. And so, I was quite familiar with it. I think the religious tradition was more, it could have been almost any religious tradition. And I’m kind of hoping I don’t get a bolt of lightning here. It could have been anything in that it helped think about something bigger than what I was doing and who I was. I think college students by design are relatively narcissistic. And so, the tradition there was thinking outside of yourself being part of something larger, the idea of service and serving other people. And I think that was really important.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s appealing. That’s actually one of the things about Gustavus is that appealed to me while I was learning about it and interviewing here.

What about business administration? So help me understand, was like a combined program French and Business Administration, or they were two separate majors? How did you wind up putting those two together?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah, it’s just a really unique program. It’s was called the Arts and Letters program for administrators, so ALBA, and you could combine any non-business major with the business core. And French was easy, and just easy to choose because I just loved it, and got to take some courses, both at Notre Dame and then St. Mary’s College, which is the women’s school right across the road.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And so, got just some amazing professors, and also was able to take the very like one, almost one and a half years of the business major. So learning the core finance and accounting and management, and econ, and all of those things that you have to take for business [crosstalk 00:08:04].

Greg Kaster:

Well, go ahead.

Kathy Lund Dean:

I was ultimately really interested in the business world.

Greg Kaster:

Okay.

Kathy Lund Dean:

My sister is a biochemist, my mother was a nurse, and my dad was an engineer. And so, we didn’t really know anything about business. And I was quite curious about what do people do? Hearing my mom and dad talk about their experiences in the workplace as a result of managerial decisions, and workplace culture, although at that time, I didn’t know that language, but just really thinking about the impact on people that managerial decisions have was super interesting for me.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, I get that. My great grandfather on my dad’s side, he was a barber. And one of my uncles joined that business. Now, my dad became a hairdresser and he worked for a big organization actually based here in Minneapolis, kind of the forerunner of reaches in some ways, but he also ran a lot of his own salons.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Wow!

Greg Kaster:

I remember it was always interesting watching my dad because my brother and I would work in these salons as the clean up boys [crosstalk 00:09:11].

Kathy Lund Dean:

Of course, you did. Oh, my gosh!

Greg Kaster:

Clip-on bow ties. But I remember being quite interested in observing my dad as a manager, that’s what he was. Maybe because of one of his salons he had, I don’t know. But it had a dozen, he wouldn’t have said women but women working. Anyway, I find that fascinating. You just said something too, which resonates with me which is, “What do people do?” I love that. I just love going behind the scenes talking to people in all walks of life to learn about what in fact goes on. But anyway so I can get that attracted. So you graduated with a BA in Business Administration in French and then did you go right on for the master? Or is that when you worked in banking for a time?

Kathy Lund Dean:

I did. I took a couple jobs in different banks, one in Cincinnati and then one in Grand Rapids, Michigan. And it was the most interesting training ground, and it really informs what I tell students now. There’s this madness. I don’t know where this narrative came from, but the idea that students have to find the perfect job right out of undergrad, and they have to find their passion. And they should do what their passion tell them, and they should never settle. And I tell students, of course, you’re going to settle, of course, you’re going to do work that’s not interesting for you, or that you know don’t want to do, but you should think about these first few jobs as somebody paying you to learn and find something, just do something and figure out who you are in a workplace. What kind of management and leadership style appeals to you? What do you like about any organizational setting? What do you dislike about any organizational setting?

And I’ve actually done some post-graduation, quasi internships with students where they’re in jobs that they don’t really like, but they need something to sort of focus their attention and distract them. And so, we do learning objectives, like they’re doing an internship like, “Okay, so what training can you get under your belt? And can you sit in on a hiring? Would it be possible for you to sit in on a firing? Could you sit in on a performance appraisal? Or have you had your own performance appraisal? What does that look like?”

And so, helping students think about organizational experiences that will transfer anywhere.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Because there are so much in common in any organizational setting. And so, the banking jobs were really that. I learned so much about not only just business, but the financial industry. And those were not conversations that we had at my house growing up. So I remember, I was with a training group at my first bank. And one of my peer group said, “Well, so how much are you putting in your 401(k)?” Because we had to choose those HR forms. And I had no idea. And I was like, “I don’t know, how much are you putting in your 401(k)? I didn’t even know that that was a thing.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And so, really just learning the way business worked was terrific. And so, I waited four years to go back for my master’s degree at Aquinas. And it is my favorite among my three degrees, my master’s because it’s not an MBA, it was a Master’s of Management. And it was specifically designed for working managers. And the faculty, were by and large, almost all practitioners, all working executives themselves, and they all came from industry.

And so, I was working during the day in my management job and going to school at night, part-time. And I cannot even tell you, Greg how much I love that. I just loved, loved, loved it. It was so applied, I would learn something in class at night. And my poor employees were totally my guinea pigs to test everything out, right? So I’d try some motivational thing and come back to class and be like, “Wow! That did not work.” And then [crosstalk 00:13:29] and we would talk together, so it was this supportive group of people kind of all in the same place, and it was fabulous.

Greg Kaster:

It sounds like a great program.

Kathy Lund Dean:

I loved it. It was great. And so, the banks were really my managerial training ground. And well, it’s where I really gained an interest in both sort of org behavior, which is my doctoral work and applied ethics in business.

Greg Kaster:

I was wondering where the interest in ethics came out of but also, so when you started in the banking world, we’re you starting as a teller? And if you go right into management, how did it work?

Kathy Lund Dean:

So at the time, it was a managerial training program that the bank had, and if there are any listeners out there that have kids that are getting ready to graduate from college, or if students are listening, if there’s a training program, grab it because they rotated us among all of the different departments in the bank. So on the retail side, which is what we think of as branches, the operation side where everything is processed, the commercial side, which is business loans, the wholesale side, which is business to business lending. And so, I got to see really all different sides of the bank and then they would place us and I ultimately ended up managing one of the largest branches in the system, and I was like 23 years old.

Greg Kaster:

That’s amazing.

Kathy Lund Dean:

I think back at that, and I think, “Wow! That was crazy. Why would they ever put a 23-year-old in charge of a bank branch?” And it was getting that kind of responsibility quickly, is drinking out of a fire hose. And it also, I think, provoked a way of being thoughtful about the way money in our financial industry impacts people on a very, very visceral and very day-to-day basis.

And so, I think that it’s informed much of my work now in the applied ethics field because I think, certainly our financial industry needs a lot of help. And I think that getting people in that industry to think differently about their impacts, has to be the way forward because we don’t need another 2008.

Greg Kaster:

No, one doesn’t think of ethics and financial industry in the same breath, typically.

Kathy Lund Dean:

One might not. And so, that’s one of my major goals and charges here at Gustavus is helping think about that intersection of money and the financial services and business. And how do we do this well? How do we do it better than we’ve been doing it?

Greg Kaster:

You’ve been doing it. You’re the advisor to an investment club, right, on campus?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yes, the Skone Investment Club. So the club started in the ’90s, with an initial investment of about 100,000, by Terry Skone. And there are lots of these types of clubs across the country at other schools.

And the idea is using real money in a real platform to learn about investing. And also, the way Terry Skone set up our club is quite unique, that there’s a philanthropy piece of it. And so, every year, we give money back. And so, by next month, the club will have given back about $70,000-

Greg Kaster:

Oh, my God!

Kathy Lund Dean:

… in scholarship money over the last nine years.

Greg Kaster:

Wow! Back to Gustavus I assume?

Kathy Lund Dean:

I’m sorry.

Greg Kaster:

Back to Gustavus I assume? Is what you mean?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yes, it’s directly to scholarships. I talk with the Student Financial Office each year, and we, we talk about what the parameters are of those scholarships, and then they get awarded. And we have about a quarter million dollars right now under investment. And I’ve really seen a steady progression in the way the students view the idea of stewardship, which I think is really the game changer in terms of business. Thinking about it in terms of a longer term orientation, which we could talk about that later. But the idea of stewarding is very different than the idea of owning.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And I’ve seen a really steady progression in the way the students understand that. We’ve put in a social responsibility clause a few years back, and we’ve made trades based on those parameters. And the students are taking it really seriously, they’re doing a great job building a portfolio for the long-term. They want to make sure it can benefit other students. And they take it so seriously, and they are so excited about giving back. Like they are genuinely so excited about the idea of giving back and [crosstalk 00:18:53].

Greg Kaster:

And so, contributing obviously to what some call a culture of philanthropy among everybody at Gustavus, students as well. And then even when they go on to become alums, of course, that’s really cool. I knew about the club, but I didn’t know about that dimension of it.

And also, as you’re saying growing wealth and being good stewards are not mutually exclusive, right?

Kathy Lund Dean:

They are not.

Greg Kaster:

The other thing you said that I want to get into your work on ethics and the professors which we are but before we do that, just backtrack a little bit because I think what you said earlier about this is … Regular listeners to the podcast know, this has been a theme of this podcast, not intentional. But the reality that some students feel, parents feel they must have it all figured out from [crosstalk 00:19:46]. What’s my major going to be because I want to do this. It’s nutty, and it’s not the case, right? And as you’re suggesting, be open to experiences to taking a job right, that isn’t going to be the rest of your life. But you can learn so much from it, as you did in the through the banking world at a young age.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

I love to cite concrete examples to our students. And I will be citing your example, along with the others. But so you got into this work, which just sounds really interesting. I haven’t read the book yet, I want to. Did it came out this year, 2020?

Kathy Lund Dean:

[crosstalk 00:20:24] book?

Greg Kaster:

Yeah.

Kathy Lund Dean:

It was the end of 2018, and it’s been translated into the Spanish language edition has been delayed a little bit with COVID. But that will come out next year. And we’re also under contract with the University of Peking Press for it to be translated into Chinese.

Greg Kaster:

All right. Awesome. That’s great.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah, so we’re pretty excited about that.

Greg Kaster:

Co-authors, but talk to us the listeners as well, of course about what that book is about, what the research was that went into it, and what your findings are, what you hope readers will get out of it?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah, so I’m Lorraine Eden, and Paul Vaaler of Texas A&M and the University of Minnesota respectively, are my co-authors. And we got together at our big Professional Association, the Academy of Management, as part of an initiative on ethics education. And we were asked to blog about different issues, very applied, again, issues that we encounter, ethical issues that we encounter in our profession. And so, particularly those things that we don’t think about as having ethical dimensions. And so, our work is generally the sort of the three legged stool, which is the research teaching, and professional life. And so, we trade it off a lot. I generally wrote more about the ethics in teaching. So it wasn’t teaching ethics as a discipline. It was ethical issues in the practice of teaching. And that was my first experience blogging in that writing form. And it was so much fun to write. You don’t have to put it all in citations. And this very careful academic writing style. It was very personal.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, exactly. It’s nice to be free of those academic disciplinary constraints when writing. You were blogging, go ahead.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah. So and then we decided, someone suggested to us that it would be a great book. And so, we put some of the blog posts, we edited them and got a publisher. And it’s been really interesting to see the feedback there. We wanted them each chapter be very short, we have sort of a catalyst issue, each chapter has a particular issue. And then we have some discussion questions, we have some additional resources. It’s things I think we don’t really talk about in the academy, and bringing things into the light. And being willing to talk about some of our dirty laundry is the only way really, we’re going to get better at this. And so, things like how should graduate students and their advisors work together? There are inherent power issues that create de facto ethical issues, especially when students graduate. We know people whose advisors still insist on being co-authors on papers years after the student has graduated. And what do you do about author order? What do you do about massaging data, or as we say, “Sort of beating the data into submission, mining the data.” Where’s that line?

So there’s lots of things about the research we do. But the teaching one, I think is particularly interesting for me, having encountered issues of, for example, equity. How can you treat students fairly, and yet, understand the different places and spaces they come from? And so, how do you think about exceptions in the classroom? How do you think about using your position of power inherently in the classroom? And so, it was really interesting to think about the issues that we encountered all the time. And it was another really timely thing like my master’s degree, I would encounter an issue with a student. And then I could blog about it, like right away. And so, it was really fresh and it was very timely, and just really gave a platform as a writer to think through pretty complicated issues.

Greg Kaster:

It’s even more timely, I would argue with COVID, the pandemic because there is all this blogging, writing, talking about what are our obligations as professors? I’m talking about higher ed. And to our students, to ourselves, to our institutions at this moment, right? So for example, is it ethical to assign grades, right?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Right.

Greg Kaster:

Under the current circumstances, so I wrestle with that a lot like not like everybody right now. To what extent should I alter my expectations, given the realities students are facing right now? Which are anxiety inducing for so many of our students, to say the least.

Kathy Lund Dean:

I think, everything that’s happening with COVID is an ethical issue. Honestly, Greg, I agree with you 100%. There was an interesting conversation that was floating around about forcing students to turn their cameras on.

Greg Kaster:

Oh, yeah.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And what is that? Is that the right thing to do?

Greg Kaster:

Yeah.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And we want our students to engage? The idea of forcing someone to turn a camera on seems nonsensical to me, given what we know, given what we learned last spring about some of the surprising things our students bring. I think we learned a lot about access. I think we learned a lot about our assumptions of internet access, I think we learned a lot about the assumptions of the home life.

Greg Kaster:

That’s right.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Food security, medicine security, safety, we’ve learned a lot about where our students were coming from. And yet, in the interest of engaging students, I think it came from a good place. But I think it’s also one of those great issues were thinking through the implications of what you want to do. It’s required, it’s absolutely required and I love your catalyst questions, you just said, “Should we assign grades? What do we owe students? What’s our obligation to students right now?” And all of those are inherently ethical issues.

Greg Kaster:

Agreed. Yeah, they’re not. I go back and forth in my own head. I was just thinking some cases I’d like, could I force you to turn your camera off, please?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Exactly.

Greg Kaster:

[inaudible 00:27:39].

Kathy Lund Dean:

Well, and what do we owe students if they get sick? How do we keep them safe? If students are afraid, if they don’t want to come to campus, I think Gustavus has created among the best set of policies that I’ve seen among many different institutions that I interact with. And some schools have not done this well. Yeah, I think we have done it well.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. I’m speaking for myself here, grateful. I’ve said this before on different episodes of this podcast, grateful that I was not forced by my institution, Gustavus to teach online or teach in-person, right? Or hybrid. That we have some latitude, which not all professors do.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

I’ve chosen my own case to teach all online, again, with a great deal of regret. But there it is. Yeah, I think too, about the students who are doing the work, and then students who, this is an ethical issue too. Students I’ve had before that I know tend not to do the work and am I really going to cut them as much slack as maybe I should be? And am I being fair to the other students? So yeah, it’s interesting to think about how so much of what we do, everything we do really is informed by ethical decisions, whether we’re aware of it or not.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah, and it’s that awareness piece. And I think that was really the key for all of us in writing that book because we’ve all seen graduate students not progress. We’ve all seen people flame out because of not the right response to an ethical issue. And I think there’s just something we don’t talk about in graduate schools, and we’re not talking about the way to think through some of these issues. With some really, career impacting kinds of outcomes.

Greg Kaster:

Right. I’m just thinking it should be required reading graduate program.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Well, we think so too, right? But we’re trying to get it through the professional associations and into some graduate programs and just create a space where people can talk about it in a risk-free way, and before it hits them in real life.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Let’s talk about sort of a real life a little bit more in organizations and ethics. I don’t know, obviously, this is a huge topic, but just your sense of we mentioned the financial industry, but every industry, right? Every organization has to deal with or shouldn’t deal with, doesn’t always, ethical issues. What’s your sense of how well the for-profit sector is doing on that? There’s this phrase corporate social responsibility, for example. I know an alum who was a history major, who got involved with that through working for Target. How seriously, are organizations taking ethics, do you think?

Kathy Lund Dean:

That is a very big question, and it has I think, a massive range. So let me preface that because it’s the essential question, I think. In my graduate program at St. Louis U, we had a business school major. So organizational behavior, and it had to be supplemented by a formal minor, you had to register for a formal minor, and it was preferably out of the business school. And so, again, having been in the financial industry, and I had also owned a small partnership firm, I really wanted to be able to frame business, within sort of the great thinkers of ethics. And SLU was a Jesuit institution, so when you do ethics, you go to the philosophy department. And it was like toggling between two different planets.

The business school, come to find out philosophy departments don’t like PowerPoint, like maybe they do now. But back then, it was completely, completely unacceptable.

Greg Kaster:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Kathy Lund Dean:

And it was so interesting, but I left. The courses I took they’re completely informed the way I think about business’s place in the world now, and how to have conversations that are yes and. So corporations make money, you need to make money. Corporations create value, it drives really our whole way of living. And corporations now hold more collective power than most governments on the planet.

Greg Kaster:

Exactly.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And so, there’s a responsibility in that power as corporations, resources, and impacts have grown, that has to be consistently drawn upon. And I think there’s a great Bill Gates, quote. He says, “When you have money in hand, only you forget who you are.” And I think that’s true. And so, kind of to address your question, I want to make the distinction that I think is really important between capitalism as a system and corporatism as what has become a pretty dysfunctional way of life and a dysfunctional way of thinking about stewardship.

Capitalism is the most successful economic system in human history. It’s a very complex thing. And if you look at how capitalism has changed people’s trajectories all over the planet, it’s helped change that very grinding and sort of systematic poverty, turning that into micro enterprising. We’ve got lots of new organizational forms that are out there, like the benefit corporation, which is a corporate form that allows philanthropy as part of their profit making, what they do with their profits, which is something that regular corporations are very limited in what they’re able to do legally.

Greg Kaster:

Yes.

Kathy Lund Dean:

There’s the social entrepreneurship model, where they’re making money. Social entrepreneurs make money using business models, and they’re designed to really fix truly entrenched social problems that 100 years of charity and NGOs can’t fix. We’ve got social entrepreneur corporations creating clean water. They’re creating corporations that increase health care access. They’re helping get rid of pollution. They’re doing renewable energy innovations using the profit seeking model in different ways is really the future. They’re making money. For sure, these are for profit organizations, but the way they use the value they create, and the type of products they make are fundamentally different. They’re fundamentally changing our world.

I just read about an organization called New Light Technologies. And I just think these people are geniuses, they’ve created an actually carbon negative type of plastic that it’s for knives and forks and plates, and you can put it in your dishwasher. But if it ends up in the ocean, the microbes eat this product, and it dissolves. And it’s feeding these microbes, and it’s dissolving in the ocean. And so, it’s genius, it’s absolutely genius. They’re going to make money, and they’re going to help fix the plastic issue in oceans. And so, we have all of these forms of companies and business that are finally getting on board. It is beyond corporate social responsibility. So CSR is essentially, a thought that you run the company status quo, and then you help with social issues with part of the profits that you make to be a good citizen.

Greg Kaster:

Okay.

Kathy Lund Dean:

That’s one way of doing it. I think the future of corporate structures and really, the types of companies our students like this generation, want to work in, are the ones that are inherently as part of their functional design, addressing issues. And that’s the intersection with sustainability.

I think, this is me. And based on all of the work that I’ve seen, I think the key issue between capitalism and corporatism is the time orientation. We simply have to stop thinking about quarterly earnings, quarterly bonuses, quarterly output. When you move that timeline out, 10 years, 15 years, 20 years, all of your activities change, your priorities change, the way you use your organizational resources totally changes.

Greg Kaster:

That is so important because there just so much emphasis on the short-term, right?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

Make money now for this quarter. Now, you sound to me, and you’re making me feel good, by the way.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Oh, good.

Greg Kaster:

You sound optimistic about this new form. And you said something important too, make sure listeners understand that this is not a corporation engaging in the status quo and doing some good work for the community. This is, as you said something. It’s built into the design of the-

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

… corporation.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

And what makes you optimistic that this is the future? Is this going to change fortune 500 companies, do you think? Or is it just going to be all these sort of micro smaller corporations engaged in this?

Kathy Lund Dean:

No, it has to be. It has to be everybody. And there is a great TED Talk. One of our huge strategic Titans, he literally, I can see it on my bookshelf, he wrote the book on corporate strategy, his name is Michael Porter. He makes a compelling argument for why sustainability has to be built in as a sustainable competitive advantage because people are finding better ways of making a product that accrue to the bottom line.

And so, one of the one of the core outcomes in the set of assignments that we do in the business ethics course, is helping students make the business case for doing something right. And so, you can say, “This is the right thing to do. This is the moral thing to do.” And we’ve had a couple hundred years of that, and it really hasn’t moved the needle. What you have to appeal to, is the idea that doing the right thing actually makes business sense.

Greg Kaster:

Right, exactly.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Right. Sustainability accrues significant cost savings, both on the front end in terms of getting the raw materials, and increasingly on the back end when you’re disposing of things. And so, how can we reuse these things? There’s inherent cost savings there.

So there is an organization one of my favorite case examples is Interface flooring, and they are the world’s largest supplier of actually the type of carpeting that we all probably have in our offices, that prefab squares of carpet.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah.

Kathy Lund Dean:

They have found a way and carpet is very petroleum intensive, the old way of making it used a lot of lots of oil, it was almost impossible to break down. The waist and the pollution were gargantuan. But the owner and the founder of that firm, decided, “We’re not doing that anymore.” And so, they are going to be completely renewable energy. I think they may have already gotten there. Zero waste with these products. And he says it saved them during the recession because they were so efficient, and they had learned how to manufacture this very durable product for less money. And they didn’t have the cost structure of again, disposal and waste and all those things. And he said, the competitive advantage that that gave them literally saved the company in the downturn.

And so, what Porter says, and this is why I’m hopeful, Greg is that once we build in the idea that sustainability is functional, that there is the business case, it’s a business imperative, that you start making things in a sustainable way, as a competitive advantage. That’s going to move the needle.

Walmart isn’t stocking responsibly harvested or farmed food or organics because of an ethical position. Let’s make no mistake about that. They’re doing it because customers demand that.

Greg Kaster:

Exactly.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And it’s accrued to their bottom line.

Greg Kaster:

That’s okay, and that touches on my next question. I think I know what you’re going to, so your answer is probably, yes. But that this is scalable up to a huge corporate like Amazon or Walmart. This is I guess Amazon’s at least rhetorically, making moves in this direction. This isn’t just going to be limited to small companies, boutique companies, or whatever.

Kathy Lund Dean:

No, it can’t be. We have companies like Mars, Incorporated. Yes, the M&M company. You should see their website. They are unapologetically all involved in social issues. And we’re going to see more organizations like that. There’s this very radical question out there, and it’s gaining a lot of steam. And it’s really moving from sort of … So the radical question, actually, is how much profit is enough? And that type of question was one where you would never raise it? And now, it’s a legitimate normative ethical question, how much is enough? Who are the other stakeholders other than shareholders? Who else do we need to be worried about here?

We’ve got activist shareholders that they’re just not putting up with it anymore. They don’t want to read about the terrible things that companies are doing. And so, shareholders are getting very, very savvy. They’re banding together and demanding these kinds of changes. And so, we-

Greg Kaster:

Radical question. Sorry, that is the radical question.

Kathy Lund Dean:

It’s the radical question. How much of what we’re able to earn, do we keep before it has to be shared?

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Kathy Lund Dean:

What kind of work life, what kind of work environment do we owe people? And those are more normative ethical questions.

Greg Kaster:

Either they’re wrapped up in this question of what is progress, right?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Right.

Greg Kaster:

So is progress only an economy, for example, that is growing at a certain rate every year, even if that ultimately is not sustainable for Planet Earth, for example?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Right.

Greg Kaster:

It shows you how difficult this has been to say that it is a radical question. I agree with you. But the fact that to ask that question is radical tells us, wow!

Kathy Lund Dean:

Right. But I also think we’ve got so much more awareness of those success stories. And I’ve even seen it in the last like 10 or 15 years. The idea that there is a limit and the idea that it used to be CSR, social responsibility was the only way into this conversation. And now you get again, companies like New Light, they’re going to a make a gazillion dollars, and they are going to fix an entrenched problem, we simply can’t Fix without innovation. And it’s just amazing to me to see what’s happening.

Greg Kaster:

I want to go buy Michel Porter’s book to reinforce the optimism you’re saying.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Well, even his newer work is in healthcare. And it’s a completely unsustainable model.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And so, how can we make in the Nobel conference this year, how can we make these dramatic innovations scalable? And yesterday, I was listening to these speakers, and I was able to grab some screenshots. Much of the conversation is about scalable engineering, scalable manufacturing.

Greg Kaster:

It’s the current conference on the Nobel conference on cancer.

Kathy Lund Dean:

On cancer. Yes, on these very exotic and hugely expensive treatments, how do you scale that? And the conversations they were saying, it’s exactly what we talked about when we talk about manufacturing.

Greg Kaster:

Well, it’s-

Kathy Lund Dean:

It’s exactly the same thing.

Greg Kaster:

I’m nodding and my body is nodding. Absolutely. I was thinking of you and me knowing we were going to speak to it. Yes, I had the exact same thought, “What am I listening to here?” I’m listening to a scientist or doctor both talking about manufacturing, right? Whether it’s manufacturing, but it’s manufacturing cells.

Kathy Lund Dean:

It’s amazing. Like it makes my head explode.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, exactly. It’s nice, exact same issues. I loved it.

Kathy Lund Dean:

It is. And I think that this is the capitalism right now, with this enormous problem of inequality. This is the one Adam Smith feared. And I used to say, Adam Smith wouldn’t recognize the system that we have at work today. But that’s actually wrong. He’s certainly recognizes it because he talks about his worst fear for the capitalist system. In chapter one, like page 60 or four. He talks about some of the problems that are inherent in the system that wealth compression, worker alienation, wealth hoarding, wage stagnation, loss of worker power and voice. It’s all there, right in chapter one.

Greg Kaster:

[crosstalk 00:47:26] when that comes out, something like his book, it’s all there. Yeah.

Kathy Lund Dean:

It’s all there. And so, when I tell students when they say, “This is not capitalism.” I say, “Look Adam Smith saw this happening 300 years ago. And so, you need to read that, go back to the source and see what he was worried about.” And I think, again, it’s gaining so much more awareness, that one, it’s destabilizing as a society to have so much wealth compression. And two, there are other models, like we can do this.

And so, I’m very hopeful. They’re very entrepreneurial, this generation. They’re the ones driving this, and they’re deciding, “I don’t want to work in a company that pollutes streams, I don’t want to work in those companies, I want to be part of a solution.”

And you mentioned Amazon. I do travel courses, where I connect students with local alumni groups in the country. And one of our J-Term courses was Seattle. And we have lovely alumni at Amazon. And the amount of energy, time and research that they’re spending, getting rid of their footprint because of course, they know they have a huge, huge, huge footprint. It’ll be there, they will find a way where it’s either carbon neutral, or carbon negative. And it’s not going to be long from now. And they will set the stage and completely set the standard for everybody else.

Greg Kaster:

I don’t want to sound gloomy, but not on our side.

Kathy Lund Dean:

It’s not, no.

Greg Kaster:

I want to go on for another hour just about this, but it’s fascinating. By the way, my sister-in-law works for Amazon.

Kathy Lund Dean:

It’s amazing.

Greg Kaster:

I do want to say a little bit about, I know you’re not doing as much research in this area you were telling me before we started recording, but your work on religious discrimination within organizations and the resolution of such discrimination disputes. You’ve done a TED talk on that which I urge people to find.

For me, what I remember reading about, I don’t know how many years ago, but organizations where there were sort of required Bible study or-

Kathy Lund Dean:

Oh, yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Just terrified of that. How much of this is … Some people listening might think we’re talking about your inability to be a Christian, right? That’s one of the narratives, right, that Christianity is under attack. But what do you mean by religious discrimination? What’s your work been about? If you can give us a brief summary.

Kathy Lund Dean:

I can, it’s some of the most interesting work that I’ve done thus far. And we wanted to look empirically at what was happening in organizations in terms of religious expression.

There used to be a non-work self and a work self, right? We would compartmentalize certain things that were taboo or unacceptable in the workplace. And religion used to be one of those. Having children was another one of those. Marital status, all of those things, you were supposed to bring this sanitized version of yourself into the workplace. And in the ’80s, and ’90s, we decided we’re not going to do that, that’s too hard. And so, we bring ourselves into organizations, and that’s created a lot more managerial challenge in managing that kind of diversity. And so, we’re thinking about religious expression and religious identity as part of diversity initiatives and organizations.

And I was really curious, I wrote, part of my dissertation was about this, but I was really curious about how is this working? How is religious expression working after 9/11? And so, the data, and I do not recommend this, I took all of the Title VII legal decisions on religious discrimination disputes from just prior to 9/11. So I think January of 2000, up through, I think I had about 14 years of data and analyzed those for what was actually happening in the case. What were the case facts? Who was being discriminated against? What was the form of discrimination? And what was the remedy? And I used the district courts, which is the level just below the Supreme Court because the Supreme Court here has so few cases.

Greg Kaster:

Sure.

Kathy Lund Dean:

So it’s essentially the end of the line in many of these is de facto, our circuit courts or our district courts.

Greg Kaster:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Kathy Lund Dean:

And it was so interesting. After 9/11 of religious discrimination disputes skyrocketed, it was the fastest growing form of Title VII discrimination.

Greg Kaster:

Wow!

Kathy Lund Dean:

But what we found in the data was that our worst behaviors and our terrible behaviors seemed to be reserved for Muslim employees. And that may seem obvious again, particularly in a post 9/11 world, but it hasn’t changed. And we are treating our Muslim colleagues in the workplace really terribly.

And the second piece, which I absolutely did not see coming, we didn’t even theorize this was the level of anti-Semitism.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah.

Kathy Lund Dean:

We saw huge amounts of anti-Semitism in the workplace. And so, we really concluded a couple of things. Number one, Christianity is not under attack. And in fact, we found no cases in which the plaintiff was a Christian, saying that they were being discriminated against, in some of these behavioral ways, like profanity, retribution, and sometimes even physical altercations. Name calling, making sure that didn’t get promoted, all of these negative outcomes. We didn’t find any cases where it was Christianity that was under attack, which I thought was pretty interesting because as you said, “The narrative is you can’t be a Christian in the workplace anymore.”

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Kathy Lund Dean:

And we did not find empirical support for that. But I think the biggest issue that we found was that culturally, we’re just not set up for Islam. And by that, I mean, Title VII protects our religious expression in the workplace. But because we’re such an individualistic nation, we’re the most individualistic nation on Earth. According to a couple of typologies. We view the world through the lens of an individual rather than an as part of a group. Our orientation is not toward impact on a group of my behavior. Our orientation is how should I individually behave?

And if you look at our Bill of Rights, like we’re set up as an individually rights given country, right? But Islam is a fundamentally group based experience. And so, it’s nonsensical for them to say something like, “I need to be accommodated, so I can pray.” And I’m the only one. And so, you get situations where you have a group of Muslim employees, and they’re all needing to do the same thing at the same time. We’re not set up for that, there are no protections for that because then it becomes an undue hardship on the company to accommodate that, that’s the baseline.

And so, we have to really rethink the way we consider religious expression to accommodate more group-based kinds of expressions. And Title VII, just isn’t up for it.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Kathy Lund Dean:

That’s not the way Title VII was set up. And so, it’s no wonder that Muslim employees are having these experiences of not being accommodated because we haven’t figured that out yet. I’m not saying that the behavior that they’re experiencing is because of the law. That’s not right. People are being genuinely terrible to them.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah.

Kathy Lund Dean:

But our laws aren’t keeping up in a way that will protect them. And that’s really the upshot of it, is we have to think differently about who we are in terms of religious expression, and bring them under the umbrella of our very traditionally individually experienced type of religious faith traditions.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Absolutely fascinating, both the findings and the way in which it’s cultural.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yes, very.

Greg Kaster:

Individual versus group. What are corporations, at least acknowledging this or doing? Do you know, or making efforts?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah. So one of the big exemplars is actually Gold’n Plump out in the western part of our state, where some of the bigger issues are, where you have large groups of Muslim employees working in a factory or a processing or environment like that, that relies on an assembly line. And Gold’n Plump, first sort of went the typical route of firing people or not accommodating them, and through some dialogue, and through some intervention, figured out a way around it. Staggering people at different times, putting in non-Muslim employees, so that the line can continue, changing the pace of work to accommodate those prayer times.

And so, the only way this is going to be fixed at this point, are those kinds of efforts. Those community-based dialogical, how can we create a win-win solution where infrastructure in our country doesn’t really give us any ways of managing that? And so, it’s really the will of the organization. But we do have some exemplars that are figuring this out.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah, that’s neat. I didn’t know about Gold’n Plump. This hit me powerfully, one day. I’m in a grocery store parking lot here in Minneapolis, and a cab whips into the parking lot. And the driver gets out and it gets into the open space and begins to pray. I realize, [crosstalk 00:58:59].

Kathy Lund Dean:

Oh, my word! Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

Right. At first, I was like, “What’s going on here?” But it hit me. I began to wonder, yes. So you’re on the job, and how do you do that, right? And it’s different, right? It’s different than if you’re on an assembly line, let’s say versus an office setting.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah, in an office we can accommodate like. It’s been, I think, for the most part, generally, non-controversial to be able to accommodate individual prayer needs. It’s when you get groups of people, and again, our country, we’re not very good at groups. We’re not very good at thinking about impact on a group level, culturally. And that’s when we need some workarounds.

Greg Kaster:

Fascinating. You’ve done some interesting research. I can as always, keep talking-

Kathy Lund Dean:

Right, yeah.

Greg Kaster:

… about some issues.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yeah.

Greg Kaster:

By way of closing, I want to give you a chance to make a case for, you’re really an embodiment of the case for this. But for the liberal arts and to the econ management program, why have an econ management program at a liberal arts institution? Why is that important, do you think? What’s your sales pitch for it? What’s your levator pitch?

Kathy Lund Dean:

Having been prior to Gustavus, only in business schools. All of my education is in business schools. I was at Idaho State University for 10 years prior to this in a business school. And I think the conversations that we can have in a liberal arts place, are different and that’s not to say other places aren’t having these conversations. It’s just that the liberal arts are set up to having these conversations.

And so, I think one of the interesting conversations you can have with students is thinking about what is Aristotle telling us about virtues? What is Rawls telling us about the nature of fairness? And then giving students live examples, and having them work through some of the difficulties of using this time honored kind of thinking in real life kinds of situations.

Recently, in the ethics course, we talked about the ethics around using those DNA databases to catch cold case criminals, the Golden Gate Killer, that made a huge splash. There have been a number of very high profile arrests in cold cases due to using DNA. And so, we look at that as from a utility perspective, if my only outcome is getting the arrest, it doesn’t matter that those databases weren’t supposed to be used for that. It doesn’t matter how I get DNA from family members, for example, who’ve been lied to, so I can get the swab. And I can build a genealogy that allows me to arrest one of their children, for example, for the murder. Because I get the arrest, and that’s ethical.

And then we look at it from a different perspective. Is deception okay? What do you owe people, in allowing them to know how their DNA is being used? I think we’ve already hit the critical mass that we need of DNA profiles, where everybody on the planet can be identified from a genealogical perspective. We can do that now. We can build a genealogy for everybody, based on the number of people who have already uploaded their DNA samples.

And so, what are the issues with that? Is the reasonable expectation of privacy? What does that mean? And helping students see that things on the face of it. It’s a no brainer, of course, we’re going to catch the serial killer. That’s awesome. It’s a lot more complex than that, in thinking through the pluses and minuses, if you will.

And the course is designed to have them think about their values, which is in a very liberal arts thing. What’s important to you? What’s your priority? And how can you make decisions, when you get in to an organizational setting that you can supply a rationale for? Not everybody’s going to agree with you, of course, but that’s not the goal. The goal is for you to be able to build a cogent rationale for making the decisions that you do, by experiencing them now, and having a chance to think about them before you actually encounter them. And the liberal arts environment, allows that space and encourages that space of diving much more deeply into the why of a situation, rather than focusing only sort of on the solution.

Greg Kaster:

Yeah. Right, that and the emphasis at Gustavus, maybe at any liberal arts institution, but it’s explicitly so at our institution. It’s in our sense of ourselves, that emphasis on social justice, on community.

And again, I’m still a believer, I know in reality, people can come from liberal arts college and take a bunch of ethics courses and still wind up doing terrible things in life itself. But still-

Kathy Lund Dean:

Yes.

Greg Kaster:

… I think you make the case well.

This has been a real pleasure. Thank you so much.

Kathy Lund Dean:

Oh, this is great. This is the best part of my day, Greg. Thank you for inviting me.

Greg Kaster:

My pleasure. I’ve wanted to talk to you about this for so long. It’s so interesting. We’ll see you back on campus at some point.

Kathy Lund Dean:

I know.

Greg Kaster:

And everyone should read Professor Lund Dean’s book. Well, everyone that could deem at least, The Ethical Professor, and I will as well. So thanks so much. Take good care.

Kathy Lund Dean:

You too. Thanks, Greg. Have a great one.

Greg Kaster:

Take care. Bye-bye.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.