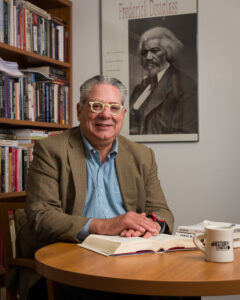

Casey Elledge, religion professor and chair at Gustavus, discusses the influence of his minister uncle and writer aunt on his trajectory, his impressive and fascinating scholarship on the idea of resurrection and Jewish texts informing the New Testament, and teaching religion at a liberal arts college.

Season 1, Episode 3: From Preacher’s Nephew to Religion Prof

Transcript:

Greg Kaster:

Learning for Life at Gustavus is produced by JJ Akin and Matthew Dobosenski of the Gustavus Office of Marketing; Will Clark, senior communication studies major and videographer at Gustavus, who also provides technical expertise to the podcast; and me, your host, Greg Kaster. The views expressed in this podcast are not necessarily those of Gustavus Adolphus College.

Greg Kaster:

My guest today is Casey Elledge, professor of religion, at Gustavus and chair of the department. Welcome. Great to see you and great to have you.

Casey Elledge:

Thanks, Greg.

Greg Kaster:

My pleasure. Casey, you’ve won the scholarship award and deservedly so. You have numerous books, articles, conference paper is really, really quite something and I look forward to hearing a little bit more about those as we proceed.

The historian in me likes to begin with the person’s past and how you came to be who you are, what you are, namely a professor of religion at Gustavus. So, if you can give us the sort of condensed version of how you wound up doing what you do.

Casey Elledge:

Well, Greg, like a lot of people you study in history, it began with growing up in a minister’s home and that’s really remarkable training and a remarkable life experience. Growing up in a minister’s home, you learn a lot about the complicated lives of people but you are also continually surrounded with the needs of the world, the needs of your community, and you’re continually surrounded by ideas, theologies, texts, sermons, traditions. So it’s a really a rich environment that’s great preparation for life but I would say it also left behind a lot of religious questions. So when I jumped into college at a liberal arts college about like Gustavus, I was just amazed at the opportunities that I had through scholarship, to begin answering my own religious questions and a lot of these sort of surrounded the Bible and biblical studies.

Greg Kaster:

What were some of those questions?

Casey Elledge:

Just where the Bible came from. Moreover, what else was going on in the world during the time when the biblical texts were written?

So my first semester of college, I can remember taking a Latin class, learning to read Latin and just being blown away at how much we could learn about the ancient world through studying Latin literature and archeology culture. So that was really a great way for me to kind of build on my early life experiences, develop intellectual questions that led me on into this particular scholarly field.

Greg Kaster:

Were you were a religion major as an undergraduate or was there such a major?

Casey Elledge:

I studied pretty broadly. I studied English literature, especially sort of Medieval and Renaissance era literature, but I also took a good bit of classical studies. So learned my Latin and Greek and took some additional religion classes on the side. So I worked most of the time within that particular triangle and found it great preparation, just for very broad cultural education but also writing and the languages and of course, things I use every day in biblical studies.

Greg Kaster:

Do you have memories of your dad who was the minister? I assume?

Casey Elledge:

Right. My uncle.

Greg Kaster:

Your uncle. Okay. Was it, I can’t remember, was it Methodist or Baptist? I’m just curious.

Casey Elledge:

He was in the Pentecostal Church.

Greg Kaster:

Pentecostal. So you remember your uncle. Do you remember your uncle writing sermons? I mean, that was something—

Casey Elledge:

That was interesting you said ideas. It was very interesting. My uncle worked more by intuition. He had books that he consulted but my aunt was a writer and an English teacher. She was sort of the scribe of the family. So I sort of had the more intuitive model in my uncle, but the more studious, discipline model in my aunt and hopefully one day I’ll learn to synthesize the two. They were both really great examples each in their own way.

Greg Kaster:

They’re perfect for teaching, perfect combination, I would argue the intuitive. Right?

Casey Elledge:

It doesn’t hurt it.

Greg Kaster:

It doesn’t hurt. Then from there you went on to graduate school, right? Graduate training, talk a little bit about that.

Casey Elledge:

That’s right. I went to Princeton Seminary and pursued a divinity degree and at that point I seriously considered going on into professional ministry. That’s sort of where I thought I was headed. However, I became involved in an academic project dedicated to the Dead Sea scrolls and publishing many Dead Sea scrolls documents that had only been released to the public in the early 1990s.

Through that experience, I probably learned my gifts were a little better for the scholarly domain. At least anyway, Greg, sometimes when I’m sitting at home with Becky, my wife, and talking about, “Well, should I have been a minister?” Her answer is frequently, “You don’t have the personality for it.”

Greg Kaster:

But you do have the voice as I’m sure you knew. That’s funny. Let’s move from that to some of your scholarship. In 2017, you published this book with Oxford titled Resurrection of the Dead in early Judaism, 200 BCE to CE 200. Talk a little bit about that. I’m especially curious about the resurrection of the dead part.

Casey Elledge:

Sure. One of the ways we study New Testament literature and Christian origins is to learn all that we can about the culture in which it arose. We tend to call that culture early Judaism or ancient Judaism. It is the many diverse forms of Judaism that existed within the Hellenistic and Roman era. So sort of before a rabbinic Judaism in 200 CE.

So one of the very interesting ways to talk about the continuity’s of Christian thought with the Judaism of that era, is through focus on resurrection. Resurrection is a premiere instance in which early Christian theology was directly shaped by the diverse Jewish theologies that existed within its context.

Yet at the same time, the early church, the first Christians, while they sort of inherited this Jewish belief through their own context, there were also new and developing ways in which they saw it in a new way, in light of the particular features of Jesus’ own life and the Easter experience of the early church.

So it’s a great way to talk about continuity and change within the era of Christian origin.

Greg Kaster:

You’re making me very happy. I often talk with my students about the seven C’s of history, three of which are context and change in continuity.

Casey Elledge:

You would be correct to note my scholarship tries to be very historical. Even when we are working with a belief or a doctrine or an idea like resurrection, there are very good reasons to approach such beliefs with a view to history, with a view to background, with a view to context, and that doing so I think lends an even deeper appreciation for those particular beliefs when we understand where they were coming from and also how they develop and changed.

Greg Kaster:

Exactly. I agree. Then what about your current work, which I think, is it published yet the latest book with Oxford or it’s called Early Jewish Writings and New Testament…

Casey Elledge:

I have a complete draft of that book that I polish from time to time, once a week or so. It’s basically ready to go when the editors are ready to work with it. But this is a more general audience book and it’s geared sort of toward upper-level undergrads or maybe lower level professional school students.

Basically what it does is it introduces some of the literature that a reader of the New Testament would want to know from the Jewish realm during that particular era. So often these texts go by the names of Apocrypha, pseudepigrapha, Dead Sea scrolls. We also know particular authors who wrote voluminous works within this environment, such as Philo of Alexandria or Flavius Josephus the historian. So the book helps people at these particular levels understand what those documents are, the issues they deal with and how those may be very important for helping us understand New Testament literature.

Greg Kaster:

Sounds great and congratulations on that, as well as the earlier book.

Casey Elledge:

It’s been fun to write and it’s been a lot easier than the resurrection book. The resurrection book, I was way out in the esoteric, certain apocalyptic text.

Greg Kaster:

Resurrections are hard.

Casey Elledge:

This has been much more close to teaching and close to the kinds of students we work with at the college. That’s a perfect transition to another question I had for you, which is what is it about teaching religion at a liberal arts college that you think is important but that you’ll also enjoy.

I think one thing that’s challenging, interesting, rewarding, is that this is a domain in which there is already sort of built in a great deal of prejudice, misunderstanding, rumor, innuendo. Stuff they told you. Things that your grandmother told you. Things that your uncle said to you. And yet the student is in a really important position in life, which is to learn to think for oneself about very important matters.

So when we enter the classroom in this domain, we want to make sure students have the opportunity to acquire some basic tools that help them find their own way, find their own path of critical thinking when it comes to religion and in so doing, hopefully empower them to sort of work through the haze of misinformation and stuff that everybody’s been telling them.

It’s a great opportunity to be able to contribute that sort of experience for students.

Greg Kaster:

Are most of the students, Christian, by background? We have Islamic faith here as well. Again, maybe some Judaism too. I’m not sure?

Casey Elledge:

That’s right. That’s right. I sort of have learned over the years, expect anything when you go into the classroom. The demographics of the college are mostly Christian and within Christian, it’s sort of mostly Lutheran, than Catholic, than many others. We do have Islamic students in the class and I would say over the course of my career, we’ve probably seen those numbers increase. We have people of no particular traditions and things that would take too long to explain over this particular conversation.

So at any rate, Greg, it’s really a place where we can kind of expect the student’s background to be all over the map.

Greg Kaster:

Do you find yourself getting pushback from the students as you challenge, I assume challenge some of their preexisting notions, beliefs, misinformation, all those?

Casey Elledge:

Sometimes and when that happens, I view it as a positive.

Greg Kaster:

Right.

Casey Elledge:

I mean, that’s a student taking control over their own way of thinking and creating a conversation with me and with other people in the class. So I find that to be very positive.

Greg Kaster:

I agree with you.

What does the typical religion major do after graduation? Is there sort of one time, I assume they’re not all becoming ministers, pastors?

Casey Elledge:

Correct. If we look at sort of the history of the college, it would be a traditional expectation, say 20 or 30 years ago, that a very large number of majors and even minors would go into some kind of professional ministry. That is still the case with some of our students but many more students take religion for a variety of different reasons.

It’s a great way to study the thing that is most important to many people.

Greg Kaster:

Well said.

Casey Elledge:

And to learn how to speak about that in effective ways and constructive ways. It is also a field that brings together so many other interdisciplinary areas; history, language, philosophy, culture. So I think some students enjoy it for that reason.

I like to think when I’m talking to major, sometimes that this is a field of endeavor in which literally anything is possible and learning how to study that, learning how to be able to get some handles on that and think critically about it, I think is attractive to people going into a variety of different fields.

We do have people who go in to particular service professions, whether that’s an NGO or some other kind of charitable organizations, social work. So it’s really all over the map.

Greg Kaster:

I agree. We say that about history too. What can I do with the history major? Whatever you would like, really. I mean, it opens up all kinds of possibilities.

You mentioned language and I know I’ve asked you this privately before. Tell us about how many languages do you need to know? Do you know? How many did you need to learn to do the work you do?

Casey Elledge:

Right. Biblical literature, especially the literature that I work with, the early Jewish literature, manuscripts are preserved in several different languages. It’s not like we want to put ourselves through a great deal of language study but with some of these writings that are very important for reconstructing the environment of Jesus in the earliest Christians, we may have to learn, say Ethiopic or Coptic or something like this.

The basic languages of course are Greek and Hebrew and Aramaic. I’ve also studied Syriac. Akkadian some Ethiopic and Latin. So we tend to study the languages we need to interpret particular texts.

One example, the apocalypse of first Enoch; very important, early Jewish apocalypse. We’ve got some fragments in Hebrew and Greek and even Latin. However, the only complete text exists in Ethiopic because the text remained a canonical document within the Ethiopian church in ways that it did not feature in Western Christian canons of scripture. So to study the book we got to go after the language.

Greg Kaster:

Are you able to see all of these sources online now? I mean, have they been digitized or do you have to actually go to the originals?

Casey Elledge:

Thankfully, yes. A great deal of, I would say especially important high profile manuscripts are on display. So to give an example of something like Codex Sinaiticus, one of our earliest complete copies of the Christian Bible. That you can read online, in Greek, in the manuscript, line by line.

A great number of Dead Sea scrolls manuscripts are also available online. So once again, kind of high profile, compelling, important manuscripts, everyone talks about, there’s a likelihood that it’s online.

It’s fun to do some manuscript work in class. So for example, when I’m teaching Greek, we will pull up an early copy of the New Testament, from time to time, and learn to read it in the handwritings of the ancient scribe and you had a closer sense of what it’s like to copy a scriptural document.

Greg Kaster:

I’m grateful as a historian, a graduate student in history, I had to have two languages. One was Spanish and the other was statistics. So you’re amazing the different languages you must know.

What are some of the courses you teach that you really enjoy teaching? I know you teach Greek, but in terms of religion?

Casey Elledge:

I teach a course on the Bible at the 100 level. That’s a basic introduction to the Bible. We obviously can’t cover everything in a semester, but after taking on some representative topics in the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament, then we study some New Testament texts.

There is another course. I teach, Paul and his letters. That’s basically all Paul, all the time. Getting to know how he wrote, what he thought, the environment that he worked in, in the era of Christian origins and of course the very important theological legacy that he left behind for Christianity.

I’m teaching a course this semester, Jesus in Tradition and History.

Greg Kaster:

That sounds great.

Casey Elledge:

That’s a lot of thought.

Greg Kaster:

Is that a new course for you?

Casey Elledge:

I know I’ve taught it, say every other year, for most of the time I’ve been at the college and after working with the gospel literature and some non-canonical gospel literature, we take on some historical proposals that have arisen in modern scholarship for trying to understand who was Jesus, the Jew. What was the life of this person who inspired the composition of the gospel literature.

We also look at perspectives on Jesus in non-Christian religions. So some Islamic and Jewish and Buddhist and Hindu perspectives and interpretations of Jesus, so that the student is broadly appointed with where the figure of Jesus might stand in a conversation among religions.

Greg Kaster:

That’s terrific. That sounds like a course I would take. By the way, I did take a Bible course as an undergraduate, which I loved. I can still remember the professor, Orville Baker, also taught Shakespeare and that course came in handy. When I wound up studying the language of white working men in the 19th century and found all kinds of biblical references and illusions that I would not have otherwise caught. I didn’t quite know what they all meant, but I knew they were biblical. So it helped. It paid off. This sounds like a great course.

What do you enjoy about our students at Gustavus?

Casey Elledge:

I think the students are, are people I respect, first of all, at the level of well-roundedness. In other words, the student who’s in my class, trying to figure out how to read some religious texts is probably also a swimmer, an artist, a performer, they might be involved in a service project of some type. They’re probably a major or double minor or something else in several other fields.

I think I appreciate then how the students have sort of a broad for education and whether or not they walk into my class and they’re the greatest reader of a religious text we’ve ever seen, I can understand that maybe this is a new skill that is contributing to a much larger and richer reservoir of skills that they’re developing here.

Greg Kaster:

I agree with you about the well-roundedness. It’s really remarkable and that was not me as a student. I think I tried tennis. That was about it. Thank you so much. This has been a pleasure. A lot of fun. Your work is amazing and I can’t wait to audit the Jesus course.

Casey Elledge:

Absolutely. Come on in. We got a place ready for you.

Greg Kaster:

Will do. Take care. Thank you.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.