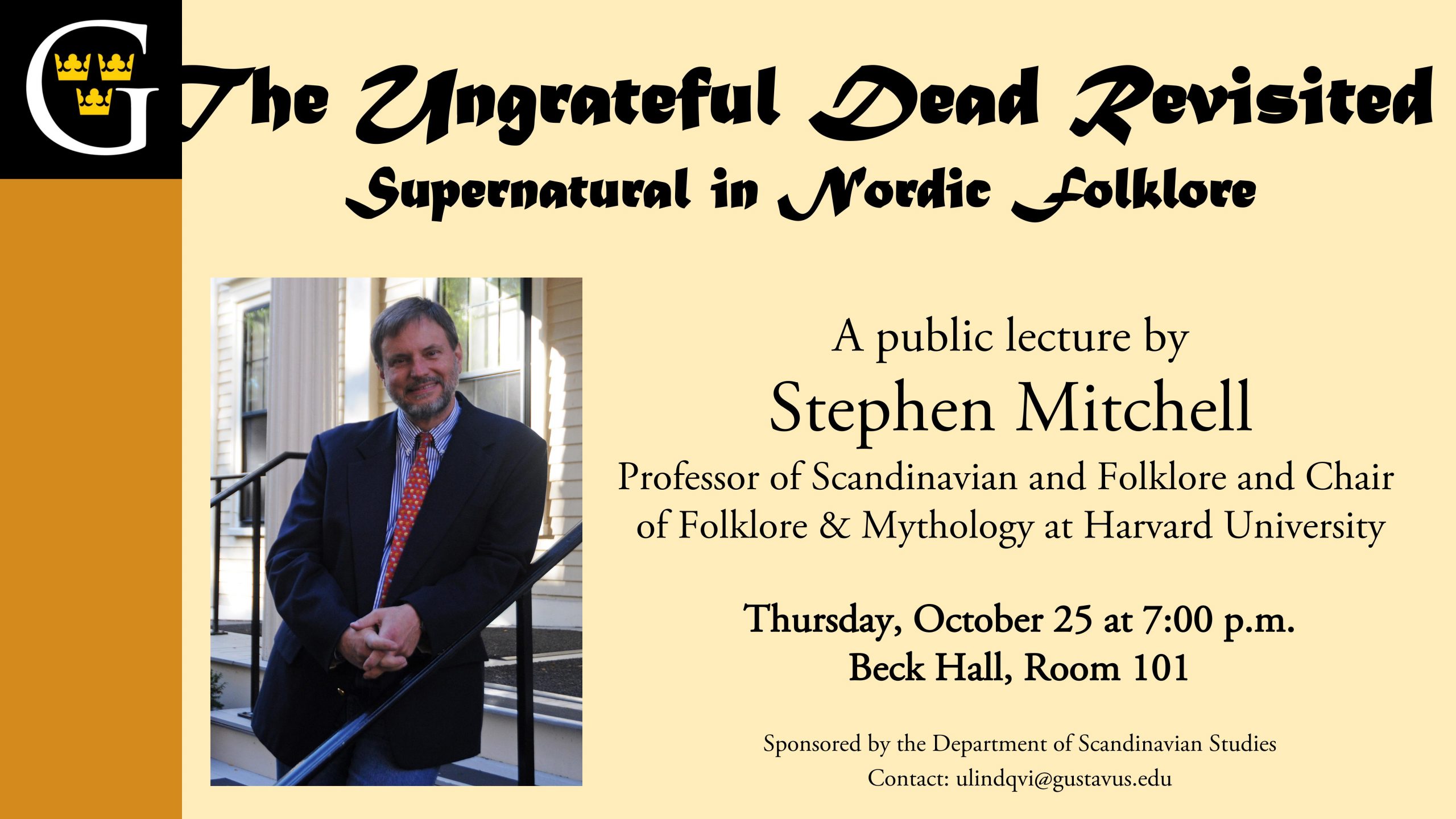

On Thursday, October 25, Gustavus Adolphus College will welcome Harvard University’s Stephen Mitchell for a lecture on the supernatural in Nordic folklore. Just in time for Halloween, Mitchell’s presentation is titled “The Ungrateful Dead Revisited” and will take place at 7 p.m. in Beck Hall 101. The lecture, which is hosted by the Gustavus Department of Scandinavian Studies, is free and open to the public.

Mitchell holds a joint appointment in Scandinavian and Folklore and Mythology at Harvard University and teaches a variety of genres and periods of Nordic culture, literature, and issues in folklore in the late medieval and early modern periods. He holds a doctorate in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures from the University of Minnesota and is especially known for his work with colleagues from the University of Aarhus (Denmark) as the director of Harvard’s Viking Studies Program in Scandinavia.

In anticipation of Thursday’s lecture, Dr. Mitchell took a few minutes to answer some questions about folklore and intercultural learning…

Q: Why is the study of historical folklore and myth important in understanding modern culture?

A: Folklore matters as it can tell us who we are and what we believe, both as regards the key roles folk beliefs, legends, and tales play in the development of our personal and group (regional, ethnic, national, etc.) identities, as well as the fact that by decocting these encoded manifestations of folklore in the doctrines and narratives we hear, tell, and use, we can in a more abstract sense better understand the worlds folklore helps construct. To put a very specific face on the practical side of studying folklore, the fact that we have a Supreme Judicial Court in Massachusetts is a direct result of the Salem witch panic of 1692 at a time when witchcraft was regarded as a crime beyond other crimes (crimen exceptum) and thus not subject to normal judicial rules, what we would today understand as “due process” and “rules of evidence,” ideas that were largely abandoned. What resulted from this juridical “witches’ brew” was precisely the kind of situation where folkloristics (the study of folklore) is not only helpful but necessary to understand what took place in Salem, that is, such issues as the belief in “spectral evidence,” the important (although not absolute) role of reputation, the character of so-called rumor (or moral) panics, the parts played by of ostension and fear, and the power relationships between accuser and accused.

Q: Who is your favorite character from Scandinavian myth or folklore. Why?

A: It’s a hard choice, but I guess I would say that I especially enjoy stories about the type of hero called the Ashlad, an English calque on Norwegian Askeladden. The same type is known in Icelandic as a Kolbíturinn “the coal-biter”; in Swedish, he’s usually called Askefisen–let’s just say it means something like “the ash blower.” He’s found in a wide variety of modern folklore texts, as well as folklore-derived works like Ibsen’s Peer Gynt; he is also well-attested in medieval Nordic texts as well (e.g., The Saga of Grettir the Strong). Typically, these are stories about an unpromising, indolent youth who in the end demonstrates his true and better character.

Q: What advice do you have for undergraduate college students as they study cultures different from their own?

A: The single most important thing any student can do to learn about another culture in my opinion is to study its language—no amount of learning about a culture in any other way competes with that. Naturally, with growing language competence should also come knowledge of the culture, its folklore, literature, news reports, and all the rest, but none of these will matter much if they are not being done in the vernacular. Cultural competence may be the ultimate goal, but you can only really get there via language competence.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.