TICKETS ARE ON SALE NOW for Nobel 52: In Search of Economic Balance.

“If everyone is given a fair opportunity to excel from creation, we will have the best chance to grow economies that benefit all.”

— John List“Can we benefit equally? No.” —Dan Ariely

“Historians tell us that in the Roman Empire, the top one percent controlled 16 percent of all wealth,” says Joerg Rieger, distinguished professor of theology at Vanderbilt University Divinity School. “In the contemporary United States, the top one percent control 40 percent of all wealth.”

Such statistics are anthems today. And there are thousands of them. The transition to a world economy has revealed polarizing tradeoffs. Our lives are highly influenced by efficiency and inequality, incentives for innovation and the needs of workers, and the policies that result from our leaders’ understanding of all of it.

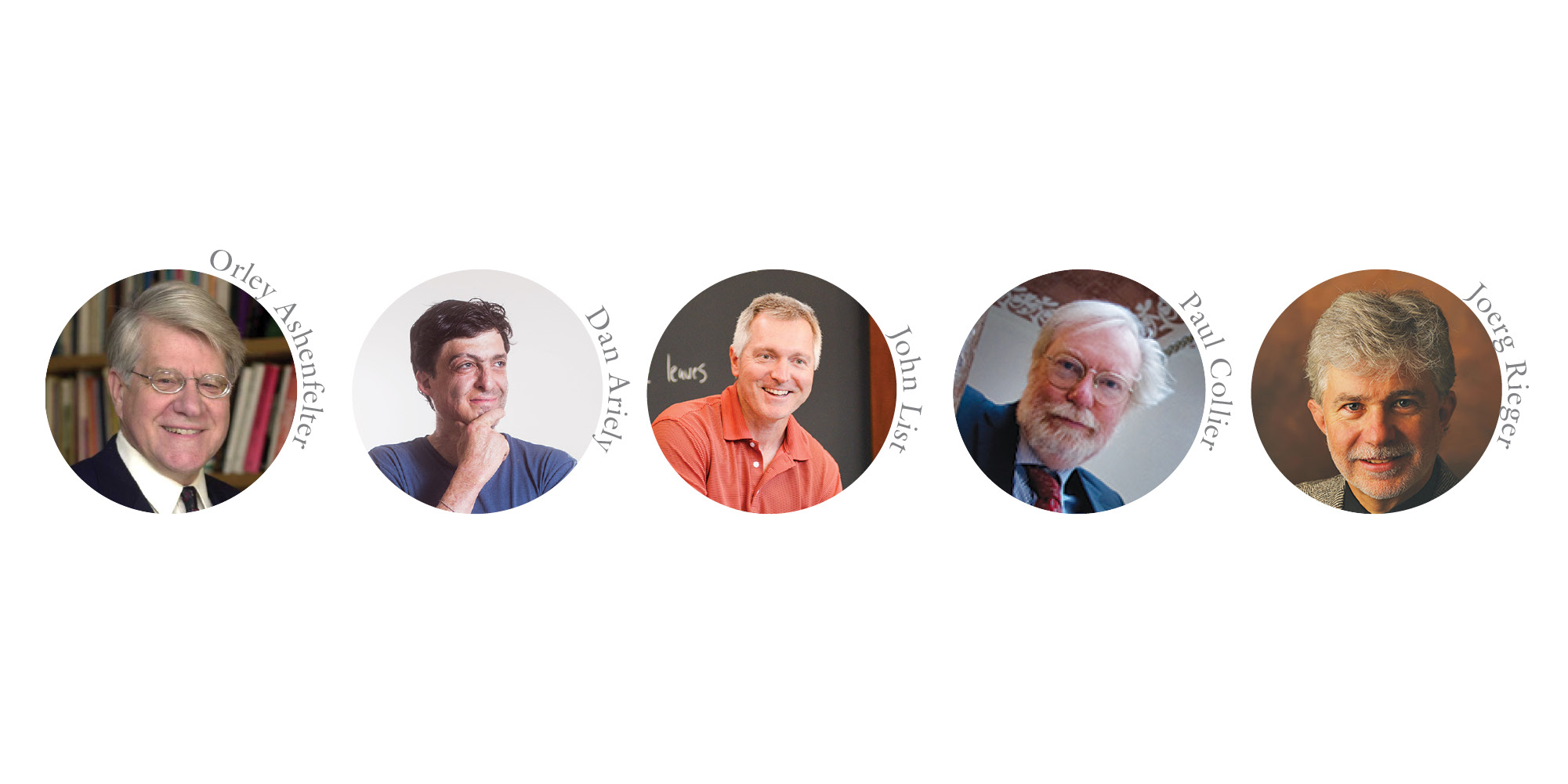

The 52nd Nobel Conference brings leading economists to Gustavus Adolphus College to explore today’s economics questions: Does inequality matter? Can we bring the prosperity of advanced economies to the rest of the world? How do we grow economies to benefit most, if not all?

It all depends on where you start, say the economists attending the conference.

In Developing Countries

“Growth in low-income countries is about catch-up,” says Paul Collier, professor of economics and public policy in the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford in England. “The key process by which the mass of the population can benefit is through tightening the labor market… This is where China has succeeded and Africa has not yet.”

Orley Ashenfelter, professor of economics and director of the Industrial Relations Section at Princeton University, agrees that China is a good example of a developing country moving towards economic growth. “And China accounts for half the world’s population!” he notes. But in China, wages are still just a fraction of those in the U.S., and it is not clear whether that country’s leaders are striving for balanced or equitable growth. Can growth in developing countries even be balanced or equal? Is such balance worth seeking? “Yes,” says, John List, professor and chair of the economics department at the University of Chicago. “It should be viewed as a meritorious policy objective.” And the best chance for this, he says, “is by focusing on human capital acquisition in the early years.” In other words: create an appropriately skilled, educated, and experienced workforce.

In the U.S. and Developed Countries

Creating balanced growth in a developed country is a difficult task as well, says Ashenfelter. “Being at the productivity frontier means you cannot grow by copying others, you need to invent change.” In recent years, productivity growth has stagnated in many developed countries, creating tension over income shares. “When there is no overall growth you can only increase your income at the expense of others,” says Ashenfelter. “It is unclear how government or public policy can help.”

But Rieger thinks he knows. “Things will begin to change if we develop new appreciation for the contributions of the 99 percent to the economy as well as to politics, culture, and religion.”

Collier seems to agree. “In rich countries, to reach to the bottom of society requires active government—taxation to finance a range of support for poor families, income supplements, and practical personal help to keep a family together while raising children.”

What We Should All Consider

All growth starts with incentives. “In most cases, incentives have very predictable effects,” says List. “We can understand and predict those effects reliably only when we understand people’s motivations.”

Dan Ariely, professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Faqua School of Business at Duke University, agrees, and also doesn’t. “Incentive methods are certainly important but we don’t understand how they matter. The type of incentives that influence us are broad—ego, motivation to do good, wanting to see success, things completed, caring about the feelings of other people…” Within these and other incentives are powerful conflicts of interest. “People just don’t see how conflicts of interest influence them, even though they do.”

Which brings up a result of competing incentives: competition. Says Ariely, “there is this general notion that competition always gets the best out of people. I don’t think we have a sufficiently nuanced view of when competition is helping and hurting. I think there are many cases where competition can actually hurt—for example, where the winner takes all.”

So, Is It Possible?

“Yes, it is possible to grow economies that benefit all,” says List. Rieger agrees: “Economies need to be measured not only in terms of the wealth they produce but also how they benefit the population as a whole and the less privileged in particular.”

“Can we benefit equally? No,” says Ariely. “What we need to ask first is how much do we invest in society, and to what degree do we invest in things that have broad benefits now, or potential in the future.” He says education is the right investment. For Collier, it’s about

“encouraging networks of young firms, supported by public support for infrastructure and higher education.” Ashenfelter, for the record, looks to new information gathered from his always-developing profession. “Probably the greatest change in economic analysis in the last few decades is the strong emphasis on empirical findings.” Research can help us understand—to a point. “Economics is a scientific field that always contains some uncertainty.”

And so all of us—economists, policy makers, and citizens alike—continue to seek answers.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.